Pages That Need Review

MS01.01.03 - Box 02 - Folder 23 - The Harmon Foundation, [undated], Part 1

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.095

In 1934, in collaboration with the College Art Association, [strike: the] Brady [strike: Harmon] proposed that the Foundation assemble a traveling exhibition called "The Art of the Negro". The exhibition, consisting of thirty-five [strike: pieces] works by twenty-four artists. It traveled to major museums and colleges across the [strike: country] nation. It was the first time that visitors to an exhibition were asked to vote for their favorite work. [strike: This which] ^Their decision was used to help^ guide the jury in making award selections. Cooperating with the New York Public Library System, ^with the advice of Arthur A Schomberg^ the [strike: Harmon] Foundation mounted the works of Black artists for exhibitions throughout the city ^of New York.^ [strike: It] ^Brady^ played an active role in placing art exhibits in the New York theatre lobbies where Black plays were [strike:running] being staged. 40 Working with ^an organization called ^ the Adult Education Committee, [strike: the Foundation] Brady placed on view over 100 [strike: works of] examples of students work ^from ^ the Harlem Art Workshop. These works, mainly paintings ^ and prints ^, were exhibited at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library where Arthur A. Schomberg curated the Department of Negro Literature History and Prints. Many Black artists had come to look upon Brady as a catalyst to promote more and better art education programs in Black institutions throughout the country. ^After the Harmon exhibit^, Black colleges and universities ^throughout the South^ began creating gallery spaces to display the works of [strike: Black] local artists. When space or money was limited, [strike: the Foundation] Brady provided photographs of outstanding artistic work by [strike: Blacks] old and modern masters for gallery exhibits. [strike: The Foundation also] More and more, Brady began to place greater emphasis on [strike: promoting] improved teacher training for art teachers, the encouragement of children's art exhibits and exploration of the study of art appreciation on both the elementary and secondary levels. Increased efforts were directed toward more exposure of African art and artists, with the Foundation arranging for exhibitions of works and preparation of slides for educational use.

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.097

to Fisk University on "indefinite loan" where is remained during [crossed out: the tenure of] this writer's tenure. Upon my departure from Fisk to join the faculty of art at the University of Maryland at College Park in 1977, Brady recalled "The Toussaint L'Ouverture Series'" And approximately 140 or more of the 300 or so works of art by Black American and contemporary African artists she had "given" to Fisk at the approval of the Foundation. She then assigned the works she recalled from Fisk to the [crossed out: Museum] [crossed out: Collaborative] Board for Homeland Ministries of the United Church of Christ in New York City to be used in [crossed out: (?)] A College Museum Collaborative Program for the six Black Colleges in the South under the jusridction of the American Missionary Association, [crossed out: at the] The idea of the American Missionary Association, the only continuing abolitionist organization of its kind in the nation, administering a program for "students of Negro origin" appealed to Brady. Her own interest in the Native Americans of Sitka, Alaske and the pioneering work that her brother [crossed out: did] engaged in at the Sheldon Jackson Jr. College [crossed out: in Sitka] there provided the picture [crossed out: she] Brady needed to ascertain the success of the museum Collaborative Program at the American Missionary Association. Brady took this action after retiring from the Foundation. [crossed out: However], But her [crossed out: association] contact with [crossed out: various] administrators of art programs at Fisk, [crossed out: remained] Talladega and Howard remained active even after her retirement. Brady's interest in art of William H. Johnson (?) important story in the history of [crossed out: contemporary] modern

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.099

Harmon Foundation Page [crossed out: 14] 23

annual exhibits of his works, the Foundation acted as art broker on Johnson's behalf, selling some of his works and arranging for private commercial gallery shows. In 1946, when Johnson became ill in his adopted Denmark, the United States goverment acted to repatriate him. Brady arranged for shipment from Europe to New York City of over eleven hundred Johnson's paintings. [crossed out : Johnson's] His works were placed in storage but many deteriorated due to dampness and the intrusion of mice and rats. In June 1956, the Harmon Foundation legally obtained release of hundreds of boxes and crates of Johnson's works from U.S Customs. Many of the paintings were in need of restoration. Palmer Hayden, a Harmon Foundation gold medal prize winner and occasional janitor for the Foundation, assumed the work of "restoring" Johnson's paintings. The Foundation with the help of the United Negro College Fund raised enough additional funds to partially restore many works. Once the paintings were restored to their original state, the Foundation donated eleven hundred fifty-four [crossed out: works] to the National Collection of Fine arts, now the National Musuem of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, along with the gift of works by William H. Johnson to the Smithsonian.

While the programs of the [crossed out: Harmon] Foundation were light years ahead of others of thier time in improving [crossed out: human condition], the status of Black artists, the Foundation's success may well have been less measurable were it not for the efforts of Brady. She served the Board of Directors as a secretary while assuming the roles of Public Information Officer, as Acting Director went works by Palmer Hayden, Malvin Gray Johnson, Ellis Wilson, Sargent Johnson, Claude Clark and other artists whom the Foundation had collected.

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.100

Harmon Foundation Page [crossed out"15"] 24

and finally Director and Chief Executive Officer until the Foundation ^closed in 1967 and ^ ceased operations in 1969. [strike: Miss] Mary Brady acted in both business and educational matters, planning and arranging for traveling exhibitions, advertising and selling artist's works to college alumni groups and art patrons and promoting the purchase of art works by individuals of wealth to be donated to Black institutions. No detail was too large or too small for [strike: Miss] Brady's personal attention. Shortly before the opening of an exhibition at a neighborhood library, Miss Brady could be seen canvassing local stores to check on the best prices for cups and spoons for the opening reception. She eventually settled on a wholesaler who offered her a lower price. She proceeded to send a letter detailing the matter to the librarian for future use. 43 [strike: Miss] Brady was a prodigious letter writer and would das off lengthy [strike: letters] ones full of pointed suggestions and details to her friends at Black colleges and universities around the country. Her suggestions were often valuable and many were implemented when possible. 44 [strike: If she saw a need or thought there was one, she would do her best to provide.] In summary, the goals and objectives of the Harmon Foundation were realized in principle through the service programs offered. Its

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.101

Harmon Foundation [crossed out: Page 16 23] 25

original purpose was not to single art out as an area for support. That decision came about at the urging of Alain Locke and George Haynes, particularly requesting support for Black artists. [crossed out: Its] Brady thought the mission [strike: was] of the Foundation to be an experiment in inter-cultural relations. Yet, attention [crossed out: that was] paid by the Foundation to [strike: Afro -American] Black American art became the legacy for which it is now remembered. Without the support it gave Black artists, fewer of them would have had a chance to exhibit their work in various places around the country and become as well known as they did in American art circles. The attention the Foundation gave to programs in visual education, archival research and creative development among Black artists helped to establish [crossed out: Afro-American] Black American art as an important cause and encouraged ^racial and ^ national pride. The legacy of philanthropic giving the Harmon Foundation fostered became a prototype for later programs administered by the Whitney Foundation, the American Federation of Arts and more recently local and national support from federal agencies. The archival repositories of the Harmon Foundation are important resources for scholars of American culture and can be found at the Library of Congress and the National Archives in Washington, D.C., ^ the final act of Mary Beattie Brady's deaccessioning of the foundation's collections.

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.102

Harmon Foundation Page 17 NOTES

1. Harmon Foundation Yearbook 1924-1926 (June 1926), page 7. 2. Ibid, page 7. 3. Ibid, n.p. 4. Ibid, n.p. 5. Activities of the Harmon Foundation, (New York, 1929), n.p. 6. Pamphlet "Objectives of the Harmon Foundation", page 1. 7. Harmon Foundation Yearbook 1924-1926, page 8 8. Ibid, n.p. 9. Ibid, n.p. 10. Ibid, n.p. 11. Ibid, page 66. 12. Ibid, page 66. 13. Ibid, page 66. 14. Ibid, page 67. 15. "Harmon Foundation News Bulletin," (February 1926) 16. Lewis, Samella, Art: African American (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc., 1969), page 71. 17. Ibid, page 68. 18. Harmon Foundation Exhibitions 1931-1935, n.p. 19. Letter of December 27, 1927 from Otto H. Kahn to Dr. Haynes, Secretary of the Commission on the Church and Race Relations of the Federal Council of Churches. (private archive) 20. Harmon Foundation Exhibitions 1931-1935, n.p. 21. Ibid, n.p. 22. Ibid, n.p. 23. Ibid, n.p. 24. Ibid, n.p.

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.103

Harmon Foundation Page 18

25. Ibid, n.p.

26. Ibid, n.p.

27. Bearden, Romare, "The Negro Artist and Modern Art, " Opportunity, No. 12 (December 1934), pages 371 - 373.

28. Lewis, Art: African American, 114.

29. Harmon Foundation Exhibitions 1931 - 1935, n.p.

30. Negro Artists and Illustrated Review of their Achievements, Harmon Foundation, Inc., (May 1935), page 17.

31. Breeskin, Adelyn D., William H. Johnosn: 1901 - 1970 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institutionn, 1971), pages 26 - 27.

32. Unpublished paper on the Harmon Foundation by Jane S. Levine (May 1986).

33. Ibid.

MS01.01.03.B02.F23.104

Harmon Foundation Page 20 BIBLIOGRAPHY Activites of the Harmon Foundation, Inc. Harmon Foundation, Inc., New York, New York, 1929.

Bearden, Romare. "The Negro Artist and Modern Art." Opportunity, No. 12. December 1934.

Breeskin, Adelyn D. William H. Johnson: 1901-1970. Washington, D.C., 1971.

"Harmon Foundation News Bulliten." February 1926.

Harmon Foundation Yearbook 1924-1926. Harmon Foundation, Inc., New York, New York

Lewis, Samella. Art: African American. New York, New York, 1969.

Letter from Otto H. Kahn to Dr. Haynes.

Levine, Janet S. Unpublished paper on the Harmon Foundation. May 1986.

Negro Artists and Illustrated Review of their Achievements. Harmon Foundation, Inc., New York, New York, 1935.

"Objectives of the Harmon Foundation." Harmon Foundation, Inc., New York, New York.

1 Archives of Afro American Art, Art Resource Technical Services, Hyattsville, Maryland 2 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 4 National Archives, Washington D.C. 3 The Spingarn-Moorland Foundation Howard University, Washington, D.C. 5 Special Collections, Fisk University, Nashville, Tenne.?

MS01.01.03 - Box 01 - Folder 13 - Artist Biographies, [undated]

MS01.01.03.B01.F13.004

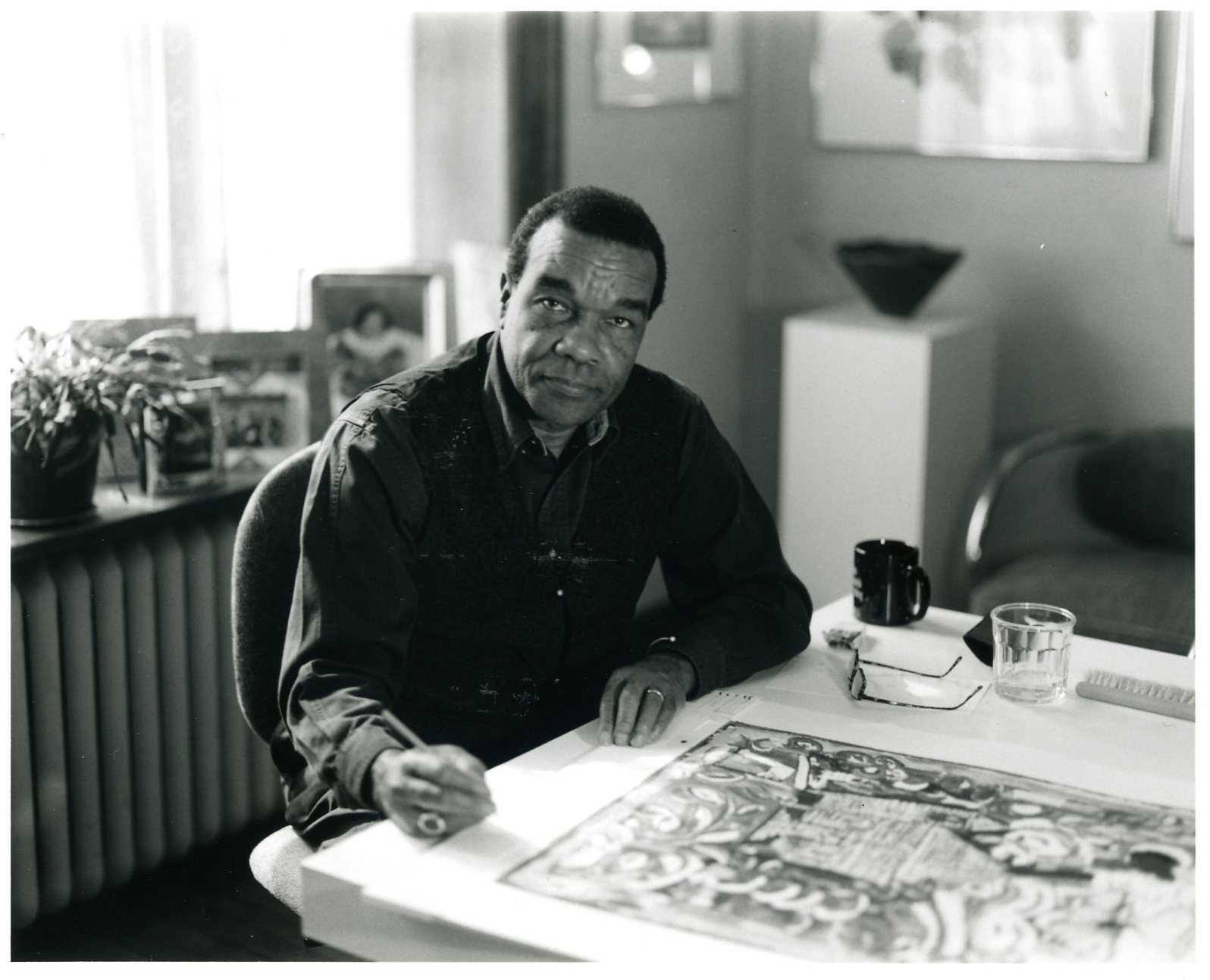

to a visible presence. Secondly, there are those visual forms that have been made by Americans of African descent with the conscious effort in mind of imitating the surface reality of a functional form from Africa without adhering to any cultural principle governing the making of such forms in African societies. These forms sanction and affirm the symbolic presence of Afr0-American culture in the visual arts and illustrate the firm historical roots of black heritage even in our own time. It is in the latter trend that one finds the adherence to a formal style of making in art that has become popularly known as "Black Art". Those visual forms which are grounded in this concept of a symbolic presence achieve a new formal expression in format similarly to that art produced by European artists who saw African art for the first time at the turn of the century, at which time, the formal dynamics of African art were copied without regard for traditional societal and symbolic function. It is now evident that the Afro-American artist, by relying upon the formal dynamics of African art as the sole pattern for his new iconographic expression, also creates a new symbol by exercising what the late Dr. Alain Locke referred to as "the return to the ancestral arts of Africa". This return must then be understood through the symbolic presence of Afro-American culture as a whole and not equared with a physical presence of AFrican art in America. History reveals to us that the black man brought with him from Africa an amazing number of skills that could be

MS01.01.03.B01.F13.008

7.

2

from Africa."

It then follows that many styles have been explored by black artists attempting to find themselves in the midst of the search for cultural identity. Often these styles are diverse in form and lack the unity of purpose commonly referred to as a school of thought or a particular style in art.

It is further evident in many cases that each artist has attempted to express in his own way his basic identity with the American experience. This (experience?) often reflected the negative aspects of being Black in America. It is, therefore, obvious that the styles of expression by black artists could not be limited to one general movement. Some artists have chosen to work specifically with black themes. Others have chosen to concern themselves with the joy of painting in abstract and expressionistic styles. There are the romantic realists as well as those who address themselves to the aesthetic mechanics of medium alone. Some of these artists have directed their work toward themes which echo an African heritage. Some of the works of the late 1920s and early 1930s best examplify the trend called Negritude. The contemporary work of Romare Bearden follows closely this trend of returning to the imagery of the ancestral arts of Africa sometimes referred to as NEGRITUDE. There are those artists who interpret African-American art to be a confirmation of the literal life-style of black people allowing no room for fantasy or imagination. As a result of the latter mentioned statement, many artists have turned to social realism causing their work to reflect