Pages

ksul-uasc-mscc208_006

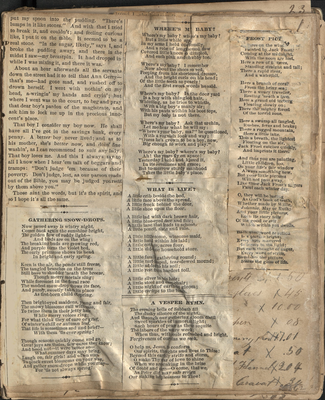

[[first column]] THE RED BREAST OF THE ROBIN. AN IRISH LEGEND

Of a[ll the m]erry little birds that live up in the tree, A[nd car]ol from the scyam[or]e and chestnut, Th[e pretti]est little gentle[man] that dearest is to me, Is the one in coat of brown and scarlet waistcoat. It's Cockit little Robin! And his head he keeps a-bobbin'. Of all the other pretty fowls I'd choose him; For he sings so sweetly still, Through his tiny, slender bill, With a little patch of red unpon his bosom.

When the frost is in the air, and the snow upon the ground, To other little birdies so beweilderin', Picking-up the crumbs near the window he is found, Singing Christmas stories to the children: Of how two tender babes Were left in woodland glades, By a cruel man who took 'em there to lose 'em; But Bobby saw the crime, (He was watching all the time!) And he blushed a perfect crimson on his bosom.

When the changing leaves of autumn around us thickly fall, And every thing seems sorrowful and saddening, Robin may be heard on the corner of a wall, Singing what is solacing and gladdening. And sure, from what I've heard, He's God's own little bird, And sings to those in grief just to amuse 'em; But once he sat forlorn On a cruel Crown of Thorn, And the blood it stained his pretty little bosom. Chambers' Edinburgh Journal.

--------------

THE COOK'S STORY.

"No," I said; "go away." I always did say that, when they came a botherin' me in the kitchen, those fellow. "No," I said; but he would come in, and stood there lookin' so wretched that I couldn't do nothin' fiercer than shake the soup ladle at him, and yell "Well, now, what do you want?"

"Something to eat," says he, as meek as a lamb. "Mother is ill, and father is dead, and she, and I, and baby, are so hungry!"

"Just the same old story," says I, "that every beggar-boy has told me for years. There, go away."

And I remember, as I said it, fastening my breastpin, that had a trick of coming undone. I knew by that that I had it on. It was one I'd had given me, and it was worth a great deal. It had belonged to a rich old lady I waited on, and poor folks generally don't have such pins. But he looked so pitiful that my heart melted, and says I, "I know you're lying, but it's just me to be imposed upon. Sit down there, and eat your breakfast, and I'll give you some scraps aferwards."

And then I went on with the puddin', keepin' my eye on the child. He was as white as a sheet, and his cheeks as hollow as a man's of eighty, and his poor little feet were bare, and the tears would rise into my eyes whether I would or no; and I felt quite wicked for havin' spoken so at first.

[[second column]] The short and long of it is, I stuffed his basket as full as full could be, and sent him off stuffed full, too; and I went back to the kitchen, and was feeling quite contented, like, and as though I'd done my duty, when, feelin' something queer about my collar, I put my hand up, and the pin was gone.

I looked all over the floor. It wasn't there. I hadn't been out of the room, and, in a moment, I knew who had got it. It was that beggar-boy. That came of harborin' beggars for the first time in my life. i didn't stop long to think. I jest pitched what I had in my hand on the floor. 'Twas only a wooden bowl; but I'd a done it jest the same, I'm afraid, if it had been a chany dish, to be stopped out of my wages. And out I went, into the street.

"Mr. Policeman," I cried, to one that was jest goin' by, by luck, "catch that beggar-boy. He's hooked my pin."

And I never saw nothing like that way that big ma nstrided up the street, and pounced on to that boy. He gave a screech, and then began to cry, and all I says to the policeman was, "Get back my pin. That's all I care for."

But that was easier said than done. The pin was not to be found. He'd throwed it away, most likely. And then I was in such a boiling rage, that I could have killed him.

"Lock him up," says I to the policeman, "and I'll appear agin him to-morrow."

And then I had to go back to the kitchen; for be a cook's emotions what they may, her missus and master won't think of goin' without their dinner--particularly her master.

Well, I kept boilin' and frettin', and wishin' I could hang the boy. And never in my life did I have such a time with missus. It was, "Cook, the meat aint done enough;" and, "Cook, the gravy is too thick." I couldn't eat a bit of any thing myself, and just sat down and cried.

Next mornin' I went to the police court and told my story, and the policemen said he'd seen the boy throw something away; and the magistrate he sentenced him to be locked up for I dunno how many days; and all the while the little rascal kept crying, and vowing he never saw the pin.

It made it so much the worse. if he had owned the fact, he wouldn't have deserved half so bad. But as it was, I was glad to see him punished, and I'd be gladder still to see him hung.

When I went home I felt better; and so, finding myself hungry for the first time since I had lost my pin, I got out the cold pudding and a bit of meat, and sat down alone by myself in the kitchen to eat them.

"No wonder missus found fault," said I, as I

ksul-uasc-mscc208_007

[[First column]]

put my spoon into the pudding. "There's lumps in it like stones." And with that I tried to break it, and couldn't; and feeling curious like, I put it on the table. It seemed to be a real stone. "In the sugar, likely," says I, and broke the pudding away; and there in the midst I saw--my breastpin. It had dropped in while I was mixing it, and there it was.

About an hour afterwards all the servants down the street had it to tell that Ann Gerry- that's me--had gone mad, and rushed off to drown herself. i went with nothin' on my head, a-wringin' my hands and cryin'; but where I went was to the court, to beg and pray that dear boy's pardon of the magistrate, and ask him to lock me up in the precious innocent's place.

That boy I consider my boy now. He shall have all I've got in the savings bank, every penny. A better boy never lived; and as to his mother, she's better now, and doin' fine washin', as I can recommend to suit any lady. That boy loves me. And this i always say to all I know when I hear 'em talk of beggars and tramps: "Don't judge, lest, as our parson reads out of the Bible, you may be judged yourself by them above you."

Those aint the words, but it's the spirit, and so I hope it's all the same.

---------

GATHERING SNOW-DROPS.

Now passed away is wintry night, Comes back again the sunshine bright, The golden flow of ruddy light- And birds are on the wing; The breaking buds are growing red, And purple turns the violet bed, The early primrose shows its head in bright and early spring.

Keen is the air, the ponds still freeze, The tangled branches on the trees Still bare to shudder 'neath the breeze, Through merry mortals sing; While foremost in the floral race The modest snow-drop shows its face, And purely, sweetly take it's place As first-born child of spring.

Then bright-eyed maidens, young and fair, The snowy blossoms cull with care, To twine them in their jetty hair While merry voices ring; For what think they of care or grief, Of winter's chill or autumn leaf, That life is sometimes sad and brief?- With them 'tis ever spring!

Though seasons quickly come and go, Great joys are theirs, few cares they know; And heed not--it were better so- What summer days may bring. Laugh on, fair girls! and often stay, To pluck sweet blossoms on your way, And gatter snow-drops while you may- For 'tis not always spring!

[[Second Column]]

WHERE'S M' BABY?

Where's my baby? where's my baby? But a little while ago, In my arms I held one fondly, And a robe of lengthened flow Covered little knees so dimpled, And each pink and chubby toe.

Where's my baby? I remember Now about the shoes so red, Peeping from his shrotened dresses, And the bright curls on his head; Of the little teeth so pearly! And the first sweet words he said.

Where's my baby? In the door yard Is a boy with shingled hair, Whittleing, as he tries to whistle, With a big boy's manly air; With his pants within his boot tops, But my baby is not there.

Where's my baby? Ask that urchin, Let me hear what he will say: "Where's your baby, nma?" he questioned, With a rognish look and way; "Guess he's grown to be a boy, now, Big enough to work and play."

Where's my baby? where's my baby? Ah! the years fly on apace! Yesterday I held and kissed it, In its loveliness and grace; But to-morrow sturdy manhood Takes the little baby's place.

--------

WHAT IS LIFE?

A little crib beside the bed, A little face above the spread, A little frock behind the door, A little shoe upon the floor.

A little lad with dark brown hair, A little blue-eyed face and fair; A little lane that leads to school, A little pencil, slate and rule.

A little blithesome, winsome maid, A little hand within his laid; A little cottage, acres four, A little old-time household store.

A little family gathering round; A little turf-heaped, tear-dewed mound; A little added to his soil; A little rest from hardest toil.

A little silver in his hair; A little stool and easy-chair; A little night of earth-lit gloom; A little cortege to the tomb.

---------

A VESPER HYMN.

The evening bells of Sabbath fill The dusky silence of the night, And through our gathering gloom distil Sweet sparkles of immortal light; Such hours of peace as theserequite The labors of the weary week; When thus, with souls refreshed and bright, Forgiveness of our sins we seek.

O help us, Jesus, to conform Our spirits, thoughts and lives to Thine! Beyond this earthly strife and storm, O make Thy star of love to shine When we are sinking in the brine Of doubt and care--O come, that we, As Peter did, may safe resign Our sinking helplessness to Thee!

[[Third Column]]

FROST PICT[URES] [Pictu]res on the win[dow,] [Pai]nted by Jack Frost, Coming at the midnight, With the noon are lost. Here a row of [fir-]trees, Standing straight and tall; There a rapid river, And a waterfall.

Here a branch of coral From the briny sea; There a weary traveller, Resting 'neath a tree Here a grand old iceberg Floating slowly on; There the mighty forest Of the torrid zone.

Here a swamp all tangled, Rushes, ferns and brake; There a rugged mountain, Here a little lake. Thus a breath, the lightest Floating on the air, Jack Frost catches quickly, And imprints it there.

And thus you are painting, Little children, too, On your life's fair window Always something new. But your little pictures Will not pass away, Like those Jack Frost's [fin]gers Paint each winter day.

O, they will be lasting As God's book of truth, Whether made by Willie, Johnnie, May or Ruth; And your little pictures, Each its story tells Of the good or evil Which within you dwells.

Each kind word or action [Is a] picture bright; Every [duty] mastered Is [lovel]y in the light; But each thought of anger, Every word of strife, Blemishes the picture, Stains the glass of life.

-------

[[handwritten]] -ints x 1.50 -gcloves x 45 x 10.00 -pen x .08 -ing [?]bou x 17.01 -at x .50 Flannel x 2.04 Cravat x 34 --562 [[/handwritten]]

ksul-uasc-mscc208_009

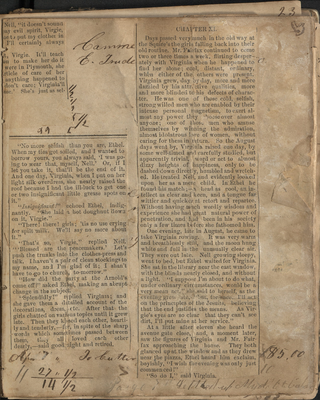

[[upper-left corner]] [[newspaper cutting]] Nell, "it doesn't sound say evil spirit, Virgie, net, put my clothes in I'll certainly always

t, Virgie. It'll teach on to make her do it were in Plymouth, she rticle of care of her anything happened to don't cae; Virginia'll me.' She's just as sel[[/newspaper]] [[handwritten]] Camme E. Trude 1/2 [?] 5 1/2

| 99 | 5 |

|---|

[[left column]] "No more selfish taht you are, Ethel. When my ties got soiled, and I wanted to borrow yours, you always said, 'I was going to wear that, myself, Nell.' Or, if I let you take it, that'll be the end of it. And one day, Virginia, when I put on her light silk overdress, she nearly raised the roof because I had the ill-luck to get one or two insignificant little grease spots on it."

"Insignificant!" replied Nell. "'Blessed are the peacemakers.' Let's push the trunks into the clothes-press and talk. I haven't a pair of clean stockings to my name, and I'm glad of it; I shan't have to go to church, to-morrow."

"How did the party at the Arnold's come off?" asked Ethel, making an abrupt change in the subject.

"Splendidly!" replied Virginia; and she gave them a detailed account of the decorations, dress, etc. After that the girls chatted on various topics until it grew late. Then they kissed each other, heartily and tenderly,--for, in spite of the sharp words which sometimes passed between them, they all loved each other dearly,--said good night and retired.

[[handwritten]] Ap[ril?] 7 " To Cutting 27 " 1/2 ---------14 1/2 [[/handwritten]] [[/left column]]

[[right column]] CHAPTER XI.

Days psssed very much in the old way at the Squire's the girls falling back into their old routine. Mr. Fairfax continued to come two or three times a week, flirting desperately with Virginia when he happened to find her alone; cool, distant, ordinary, when either of the others were present. Virginia grew, day by day, more and more dazzled by his attractive qualities, more and more blinded to his defects of character. He was one of those cold, selfish, strong willed men who are enabled by their intense personal magnetism, to exert almost any power they choose over almost anyone; one of those men who amuse themselves by winning the admiration, almost idolatrous love of women, without careing for them in return. So the August days went by, Virginia raised one day, by some well-timed and carefully studied, but apparently trivial, word or act to almost dizzy heights of happiness, only to be dashed down directly, humbed and wretched. He treated Nell, and evidently looked upon her as a mere child. in Ethel he found his match;--a head as cool, an intellect as clear and keen, and a toungue far wittier and quicker at retort and repartee. Without having much wordly wisdom and experience she had a great natural power of penetration, and had been in his society only a few times before she fathomed him.

One evening, late in August, he came to take Virginia rowing. it was very warm and breathlessly still, and the moon hung white and full in the usually clear air. They were out late. Nell growing sleepy, went to bed, but Ethel waited for Virginia. She sat in the library near the east window, with the blinds nearly closed, and without a light. "I suppose I'm about to do what, under ordinary circumstances, would be a very mean act," she said to herself, as the evening grew [l?]ate, 'but, for once, I'll act on the principles of the Jesuits, believing that the end justifies the means. As Virgie's eyes are so clear that they can't see dirt, I'll put mine at her service."

At a little after eleven she heard the avenue gate close, and, a moment later, saw the figures of Virginia and Mr. Fairfax approaching the house. They both glanced up at the window and as they drew near the piazza, Ethel heard him exclaim, boyishly, "I wish the evening was only just commenced!"

"So do I," said Virginia.

ksul-uasc-mscc208_010

[[left column]]

"Are you in earnest, Virginia?" he asked softly, bending his head slowly, until, from where they stood in the moonlight, Ethel saw his fair hair touch Virginia's.

She hesitated a moment, and then, in a sudden passionate whisper replied, "You know I am."

"Little darling." he said folding his arms tenderly around her and kissing her.

Ethel pressed her lips tightly together, but remained motionless, her sense of hearing strained to the utmost lest she should lose their low words.

"You are going away, next month," he said, presently, "What shall I do without you?"

"I shall only be gone two weeks, and you are n't going home until November You'll come and see me just the same after I return will you not?"

"I hope so," he replied.

They were silent for a few seconds. Finally he kissed her twice, and then slowly withdrawing his arm from her little slender figure, bade her good-night. S[he?] watched him out of sight. The instant [he?] was gone, Ethel ran up the back stairs [to?] her own room, and undressing with the utmost haste, crept into bed and waited to hear Virginia come up. She had not long o wait and when she thought Virginia was in bed, arose, and opening the door connecting the two rooms, went up to her bedside and asked if she might sleep with her.

"Yes," replied Virginia, reluctantly.

"You'll never be able to sleep, Virgie, with the south blinds wide open, and the moonlight streaming in like this."

"I'm not sleepy," replied Virginia, briefly, in a preoccupied way.

"Neither am I," said Ethel. "Let' slie awake and talk awhile."

"Well," replied Virginia, "but only a little while, t'is so late, you know."

Ethel made a bold dash at her subjet

"Virgie, what splended eyes Mr. Fairfax was!" she said with true womanly intention and craft.

I d[on?]'t believe there's another such pair in the world," replied Virginia.

[?] were ont late; how far did you go?

"Oh, we kept along,near the shore nearly down to Eastport Neck."

"Four hours! and did'nt he grow rather tiresome toward the last of it?"

"Tiresome!" exclaimed Virginia, "I wish we ight have sailed on forever and ever!"

[[right column]]

"V[irgie?] hush" said Ethel, putting her arm around her sister. "How extravagantly you tal[k?] [?] are excited, Virgie. He is'nt half the [?] [yo?]u imagine him. You don't care much [?] him do you?"

"He cares for me. He loves me, " replied Virginia evasively.

"Has he told you so?"

"Not in so many words, but he has given me to understand, in a hundred ways that [he?] does; and he is too honorable a

RU[A?]RY 5, 1875.

gentleman to allow a woman to think he cares for her if it were not so."

"Virgie, I don't wonder that you are atracted by him, and I don't blame you in [the?] least. He's a thourough man of the [wo?]rld, and capable of attracting any woman who did not understand him perfectly."

"[That?]'s precisely the reason I like him so well" replied Virginia, quickly. "I have seen a great deal of him in the last two [months?], and I know that he is as good and [warm?]-hearted, as he is polished and brilliant.'

"Polished and brilliant he is, I will admit. [?] are diamonds. Nothing less hard would over take such a polish."

"Diamonds are gems, at any rate, "retorted Virginia, "and rank highest."

"Yes, and are hard and cold, and as often bring pain as pleasure to their possessor."

"What do you mean, Ethel?"

"I mean that he is as heartless and selfish as he is accomplished and attractive. I mean, [Virgie?], darling, that, simply to pass away [?] time and gratify his inordinate vanity, he is amusing himself with you."

"He is not! replied Virginia angrily. "He is incapable of anything so utterly contemptible."

"Who is fittest to judge, I, who am cool-headed and look at him impartially, or you who he has succeeded in dazzling?" asked Ethel, gently.

"You and Nell are envious because he notices me to much more than he does you" repliedd Virginia, still angry and hurt.