Pages

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-006

51

in the Canadian Government; a virtual deadlock was produced. Eventually the supporters of one candidate seem to have proposed to the supporters of the other that, since they could not agree on what to do, they had better agree to do nothing. A telegram announcing this decision reached me in Reno, Nevada, on the summer of 1921 and broke my heart for the time being.

We have dwelt in previous chapters upon the theoretical considerations behind our belief in a coming new era and our plans for extensive and continuous northern exploration. But I had also been under constant pressure of another sort. The tropical explorer becomes infatuated with the tropics and either returns to them or eats out his heart deploring the circumstances that keep him away. Is is so withThe like is true of the arctic traveler. There are few who once go north who do not go alsowithout desiring to return therea second and a third time.or at least whine and complaineat out their heart with vain desire because they cannot go. On my expedition of 1913-18 I had had with me a number of men who had fallen in love with the North and who were pining to get back, there. I had told them about the indefinite plans of the Canadian Government, promising that if these materialized I would try to get them an opportunity to go along. My files are filled with correspondence begging for such chances. Two of my men, Knight and Maurer, had been specially urgent and I had promised them the first opportunities.

E. Lorne Knight was had been a Seattle high school boy who had servered capablywhen he began in 1915 forcapable three year service on my last expedition. He was fitted for pioneer work by physique and temperament and washas been popular with his companions. I liked him especially. In 1917 he accompanied me on the longest sledge trip I ever made, and in 1918, when I was ill with fevertyphoid he accompanied my second-in-command, Storker Storkerson, on one of the most remarkable of polar adventures. On that journey Storkersbn and his four companions traveled in midwinter by sledge north from Alaska about two hundred miles into the unexplored ocean, selected a substantial ice floe and camped upon it for more than six months while it drifted four hundred and fifty

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-007

*See the appendix, post, for an abbreviation of Storkerson's own story of this remarkable adventure. 52

miles, living by hunting the while and trying especially to determine the direction of ice movement in that part of the ocean. During the seventh month Storkerson, the leader, became ill. It was October, the worst part of the year for travel over moving sea ice, and they were then three more than two hundred miles away from land. But because they were complete masters of the technique of winter travel over moving sea ice floes, they got ashore without trouble. The thrilling story of the seven-month drift and the five hundred miles of sledge travel over broken see ice in going forward and back between the composite floe and Alaska is told in the appendix written by Storkerson for my "The Friendly Arctic." With the exception of Storkerson and myself, there was no man living in 1921 not even Nanseu who traveled as many miles on over moving sea ice or who had spent as many days upon it away from a ship as had Knight. Of the great explorers of the past, Perry was the only one who had excelled Knight's record.At twenty-eight he was in age, experience, physical strength an tempermental adaptability are ideal [mau] for the work he so passonately desired to undertake.

Frederick Maurer I saw first in 1912 when he was on a whaling ship wintering in the Arctic north of Canada; in 1913 he became a member of the crew of our Karluk. He was with that ship when it sank some eighty miles north east of Wrangell Island and was one of the men who spent more than six months on Wrangell Island in 1914 after the shipwrecked men landed there. It was he (as we have told in a previous article chapter) who raised the flag at the time British rights to the island ware reaffirmed on July first 1st 1914. Maurer was eager to get back to any part of the Arctic but particularly eager to get back to Wrangell Island, for his knowledge of various other parts of the North led him to consider that as one of the richest and most desirable islands. Like Knight he was at the ideal age of twenty-eight and qualified by experience, temperment, and physical strength. Shortly before I received the telegram from Ottawa saying that the projected expedition had been postponed for at least a year, I had received another wistful letter from Knight in which he said pathetically wistfully: "I have been away from the Arctic nearly two years now, and it has been quite a long two years.”

We have told ina previous chapter that In 1921 it was reported in the press that the Japanese were

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-008

53

believed to be penetrating eastern Siberia with a view to wresting it permanently from the Soviet government of Russia. Some friends of mine who had returned from northeastern Siberia confirmed the actual Japanese penetration at the time and believed in its permanence. With my great admiration for the Japanese, I took it for certain that within a year or two they would realize the coming importance of Wrangell Island and would occupy it. Since they were at that time the allies of Great Britain, it would have been all the more awkward to ask them to leave the island. The most Britain could have done would have been to suggest international arbitration, whereupon it might have been decided that, in spite of original British discovery, an actual Japanese occupation in 1921 or 1922 had more force than a half year of British occupation in 1914.

By a curious accident an old friend, Mr. Alfred J. T. Taylor, of Vancouver, turned up in Reno the day I received the heartbreaking telegram from Ottawa. I was worrying over what appeared to me the shortsightedness of our statesmen and worrying also because it seemed I was going to be unable after all to provide Knight and Maurer with a chance to go north. The appearance of Taylor cheered me, and in an hour my wrecked hopes had been replaced by a plan we thought we could carry through.

Since Wrangell Island was already British, we could keep it British by merely occupying it. As we understood international law, it would make no difference whether such an occupation had been specially ordered by any government so long as the government in question eventually confirmed it. I wired Knight and Maurer to ask whether they would go to Wrangell Island secretly and whether they would exchange their American for Canadian citizenship in order to make the occupation legally effective. Both replied eagerly in the affirmative. Since I was just then engaged under contract on a piece of work that did not allow me a day’s vacation until September, I got Taylor to undertake the actual organization of the expedition. Because the Canadian Government had decided to do

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-009

54

nothing for a year, we could not take even them into our confidence. We confided in no one except that Taylor had to place the facts before his private attorney to get qn opinion of the legal aspects of the case. The attorney told us that an application for Canadian citizenship by Knight and Maurer would not turn them forthwith British in the sense needed to make an expedition British which was led by one of them. He advised the organization of a limited liability company under the laws of Canada. This company would employ all the men who were on the expedition, and that would make the enterprise indubitably British. Later he revised this opinion, coming to the conclusion that we could not feel the undertaking safely British unless a British subject were at the head of it.in command. This led to the employment of Allan R Crawford, the son of Professor J. T. Crawford of Toronto, Canada, to be in formal command. We had previously corresponded about his possibly going north and I now telegraphed him to join me on the Pacific Coast.

Because of later tragic developments, it is important to explain here how Allan Crawford came to be selected for the Wrangell Island expedition. During the winter 1920-21 several of us had been carrying on an energetic campaign in Ottawa to interest the Government in the beforementioned large plans of polar exploration. One of the most enthusiastic was Mr. J. B. Harkin, Commissioner of Dominion Parks and at that time officially interested in the welfare of northern Canada since the game laws, which now havesince been transferred to the Northwest Territories Branch, were then under his administration. Spring drew on apace and we were eager that the expedition should sail that summer. We were, therefore, trying to get everything ready so that the moment we received approval and money from the Government we could push ahead along various lines. Our most definite success had been that money had beenWe were temporarily optimistic through having succeeded in getting money set aside for the refitting of the Canadian Government's old exploratory ship, the Arctic, and this work was actually going on in secret to the extent that the purpose of the

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-010

55

refitting and the destination of the proposed voyage were kept hiddensecret. So far so good, but it was almost equally important that we should have a staff of men ready, Mr. Harkin and I, therefore, agreed on writing a tentative stereotyped letter to the presidents of most of the Canadian universities, asking them to nominate young men trained in the sciences and recently graduated from college with whom we might confer to make up our minds whether they might be eligible for polar service.

Eventually we received replies from most of the presidents; but the only correspondence that concerns us here is that with the University of Toronto. We need not copy the whole correspondence, for its essential points are summarized in the first letter written to me by Allan Crawford.

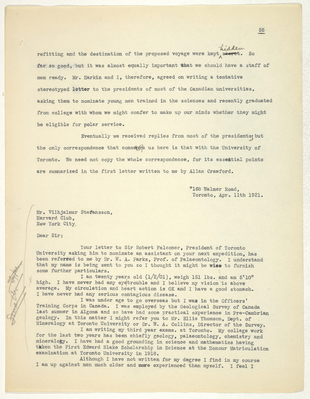

"168 Walmer Road, Toronto, Apr. 11th 1921.

Mr. Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Harvard Club, New York City,

Dear Sir:

Your letter to Sir Robert Falconer, President of Toronto University asking him to nominate an assistant on your next expedition, has been referred to me by Dr. W. A. Parks, Prof, of Palaeontology. I understand that my name is being sent to you so I thought it might be wise to furnish some further particulars.

I am twenty years old (l/2/01), weigh 151 lbs. and am 5'10" high. I have never had any eye trouble and I believe my vision is above average. My circulation and heart action is OK and I have a good stomach. I have never had any serious contagious disease.

I was under age to go overseas but I was in the Officers’ Training Corps in Canada. I was employed by the Geological Survey of Canada last summer in Algoma and so have had some practical experience in Pre-Cambrian geology. In this matter I might refer you to Mr. Ellis Thomson, Dept. of Mineralogy at Toronto University or Dr. W. A. Collins, Director of the Survey.

I am writing my third year exams. at Toronto. My college work for the last two years has been chiefly geology, palaeontology, chemistry and mineralogy. I have had a good grounding in science and mathematics having taken the First Edward Blake Scholarship in Science at the Honour Matriculation examination at Toronto University in 1918.

Although I have not written for my degree I find in my course I am up against men much older and more experienced than myself. I feel I