Pages

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-050

- 26 -

89

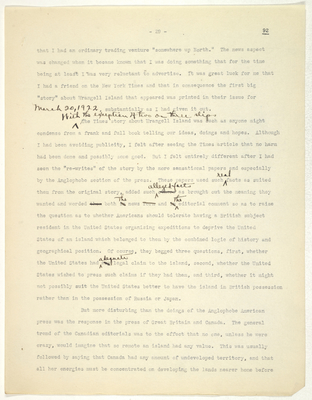

ahead of any Japanese or other occupation anyone else that year and obviously the first landing party since our own men had left there in 1914. Apparently the first thing they did after landing was to scramble up a hillside, erect a flagpole, hoist the Union Jack and read ceremonially the following: proclamation a photograph of which is reproduced herewith.

Proclamation, Know all men by these presents that I, Allan Rudyard Crawford, a native of Canada and a British subject, and those men whose names appear below, members of the Wrangell Island detachment of the Stefansson Arctic Expedition of 1921, on the advice and counsel of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a British subject, have this day, in consideration of lapses of foreign claims and occupancy from March 12, 1914, to September 7,1914, of this island by the survivors of the brigantine Karluk, Captain R. A. Bartlett, commanding, the property of the government of Canada, chartered to operate in the Canadian Arctic expedition of 1913-1918, of which survivors Chief Engineer Munro, a native of Scotland and a British subject, and raised the British flag, declared this land, known as Wrangell Island, to be the just possession of His Majesty King George of Great Britain and Ireland, the dominions beyond the seas, Emperor of India, etc., and a part of the British Empire.

"Signed and deposited in this monument this sixteenth day of September, in the year of our Lord on thousand nine hundred and twenty-one.

(Signed) Allan Crawford, commander E. Lorne Khight, second-in-command Milton Galle F. L. Maurer

Wrangell Island, Sept. 16, 1921 "God save the King."

When this the proclamation got to me through the mails several weeks later I took it as a rather inconsequential detail of a successful enterprise. But it had started a ferment in Alaska which was to bring far-reaching developments. Until the flag rarsing of the flag and the issuing of the proclamation, it does

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-051

90

- 27 -

not seem to have occurred to the crew of the Silver Wave that there were any motives other than fur trapping or gold prospecting. Apparently also they felt that the hoisting of a flag had a magic effect, suddenly changing or establishing sovereignty - the much more important landing of an outfit a few hours earlier appears to have had no such meaning in their eyes. On the voyage back to Alaska they worried a good deal, probably not so much for the fate of Wrangell Island in itself as for their own share in the enterprise, wondering whether their fellow Alaskans Americans might consider them renegades, since they had indubitably if unwittingly taken part in such momentous doings.

I should judge that when the party landed in Nome the more important citizens of that city took the flag story rather calmly, realizing that it the hoisting of the Union Jack did not do much to add or detract from the general effect of all the other things that had been done by my expeditions between 1914 and 1921. But the incident was enough for a journalist with a keen news sense, and the Nome Nugget printed a long "story" under a "scare head." The gist of it was that here had been this valuable island lying right under the nose of Alaskans these many years and now some Britishers had come and run off with it. Apparently no one in Nome had up to that time thought much about the ownership of the island, but now it seemed clear to a good many that it was an obvious and logical part of the territory of Alaska. The legend even grew up that it had been included in the Alaska purchase. Alaskans and other Americans had frequently seen it (this was true, for especially in the whaling days several ships used to sight Wrangell Island practically every year). After the subject had been discussed long enough around Nome the theory developed that it had been deceitful of us and even an international "unfriendly act" to outfit in an American port with the friendly support of Americans when the design was to get hold of an island which either was or ought to have been American property.

As said, the substantial leading people of Alaska probably took

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-052

- 26 - 91

little more than casual notice of these discussions. However, it appears that the talk the eventually crystallized into some sort of protest which was eventually sent by Alaskans to Washington.

Insert here page following

From After the landing of the party in Wrangell Island and the safe return of the Silver Wave to Nome I saw had seen no cause for doing anything special for some months, There was an election on in Canada and there was no point in trying to urge the Government to action until we knew who would be the Government next summer when the supply ship for Wrangell Island would have to sail. I felt sure of the safety and comfort of the party. My stock reply to constant inquiries was that they were as safe and comfortable as a party equally isolated on a tropical an island like such as Robinson' Crusoe's. They were doing the sort of thing that I had dreamed about doing from childhood, which they had always wanted to do, and which at least one healthy young man in every five in Europe or America would dearly love to have the chance to do.

And if I was not worrying about the situation up there, neither was I worrying about any more southerly aspect of it, when one day a newspaper friend told me that a "big story" about Wrangell Island was about to “break," and gave me the chance of publishing my version before another, probably more inaccurate, should would come from Washington. The New York Times had found out about the protest from Alaska to Washinton to the delegate in Congress and had realised the news value of it but was anxious to have not merely some story but the accurate facts.

Up to this time I had been much pleased with the absence of interest in the Wrangell Island undertaking. Those journalists who knew about it probably imagined that I was anxious for publicity on the subject and were keeping things quiet for that reason, it being the instinct of newspaper men to drag a story, out of you if you are reluctant but to be very suspicious of any information you voluntarily give them. I had not given them information voluntarily, but neither had I allowed anybody to discover that I had anything to hide. It was supposed

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-053

Insert-p. 91

One of Captain Hamar’s assistants on the Silver Wave was August Soderholm, now master of the schooner Nokatak plying in Alaskan waters for the Lomen Reindeer and Trading Corporation. He had been so much taken with Wrangell Island that he tried hard on his return to Nome to organize a party to charter a ship and go there to establish a chain of fur trappers around the island. Patriotism may have played a part (to make the occupation of the island jointly American and British) but adventure and commercial motives were doubtless uppermost. He was unable to muster a party, because the season was so late (the last week of September) that the consensus of sailor opinion at Nome was against the voyage as unsafe because of the nearness of winter. This in spite of Soderholm's strong urging that they had just returned from Wrangell without seeing snow except on the distant interior mountains, and without seeing a cake of ice at sea.

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-054

- 29 - 92

that I had an ordinary trading venture "somewhere up North." The news aspect was changed when it became known that I was doing something that for the time being at least I was very reluctant to advertise. It was great luck for me that I had a friend on the New York Times and that in consequence the first big "story" about Wrangell Island that appeared was printed in their Issue for March 20,1922, substantially as I had given it out.

With the expedition of two or three ships the Times story about Wrangell Island was such as anyone might condense from a frank and full book telling our ideas, doings and hopes. Although I had been avoiding publicity, I felt after seeing the Times article that no harm had been done and possibly some good. But I felt entirely different after I had seen the "re-writes" of the story by the more sensational papers and especially by the Anglophobe section of the press. These papers used such real facts as suited them from the original story, added such others alleged facts as brought cut the meaning they wanted and worded them both in the news form and in the editorial comment so as to raise the question as to whether Americans should tolerate having a British subject resident in the United States organizing expeditions to deprive the United States of an island which belonged to them by the combined logic of history and geographical position. Of course, they begged three questions, first, whether the United States had any adequate legal claim to the island, second, whether the United States wished to press such claims if they had them, and third, whether it might not possibly suit the United States better to have the island in British possession rather than in the possession of Russia or Japan.

But more disturbing than the doings of the Anglophobe American press was the response in the press of Great Britain and Canada. The general trend of the Canadian editorials was to the effect that no one, unless he were crazy, would imagine that so remote an island had any value. This was usually followed by saying that Canada had any amount of undeveloped territory, and that all her energies must be concentrated on developing the lands nearer home before