Pages That Need Review

stefansson-wrangel-09-26-001

stefansson-wrangel-09-26-001-058

42

that some sick people might have been still living at that time to hold them back.

Hadley considered that the entire party from the Karluk could have "had a picnic" on Wrangell Island for one or several years if the following things had keen done: The big Eskimo walrus hunting boat (umiak) which had keen placed on board the Karluk for such an emergency, should have keen brought ashore after the shipwreck. Doing this would have necessitated throwing away perhaps a thousand pounds of provisions and petroleum. This Hadley considered would have been of no consequence, for the petroleum was unnecessary in any case as there was abundant driftwood for fuel on Wrangell Island, and the food thrown away would have keen negligible because unlimited quantities of walrus meat and fat could have keen secured with the skin-boat. The hunting, or at least the use of ammunition, should have been confined, he considered, to only a few of the party who either knew already how to use rifles or showed themselves capable of learning quickly. But as a matter of fact, large quantities of ammunition were fired off by anyone who wanted to, the targets in many cases being distant birds on the wing.

It has been the rule on all exploratory journeys of our various expeditions when we have been living entirely by hunting that no shot was ever fired at an animal smaller than a wolf. Thus have we been able to maintain for more than ten years an average of over a hundred pounds of meat (live weight) for every bullet fired. Hadley thought this average could hove been exceded at Wrangell Island if a skin-boat had been available and if the shooting had been restricted to a few of the most capable men.

To the reader unfamiliar with polar conditions and even to those polar explorers who are used to living on provisions

stefansson-wrangel-09-26-001-059

43

brought from home, the story of the Karluk party on Wrangell Island seems one of unrelieved and inevitable tragedy. Of twenty-five persons involved, eight had been lost during the sixty-mile Journey from the shipwreck to the island, and three on the island itself. Nearly every venture in hunting and travel had turned out badly.

But Hadley had lived in the Arctic for a quarter of a century, taking part sometimes in the various activities necessary for self support and always associated more or less directly with natives or white people who were making their living by hunting, sealing or fishing. On the basis of what he knew about the north coast of Canada and Alaska and about Victoria, Banks and other islands where we had been living by hunting for years, Hadley insisted that Wrangell Island was by nature one of the most favorable locations in the polar regions for self support by people who knew how to avoid becoming victims of their environment, capitalizing the very conditions that to the inexperienced are handicaps and hardships. Drift logs for the building of comfortable cabins and for indefinite fuel supply are found in Wrangell Island but in none of the other islands to the north of North America; in that important respect Wrangell, therefore, excels all other islands. Hadley had never seen walrus so abundant and so easy to get (with a skin-boat); polar bears seemed more numerous than in any locality where he had been. Walrus and polar bears are the biggest game animals in the Arctic and the easiest for the skilled hunter to secure. Seals, more elusive to even the best hunters, were abundant around Wrangell Island and obtainable, of course, on the same basis there as in any other arctic country. In winter the island was separated from Siberia by only a hundred miles of average sea ice such as we are accustomed to travel over at

stefansson-wrangel-09-26-001-060

44

about twelve miles a day. On our various expeditions we have traversed perhaps two thousand miles of similar ice, generally more mobile and dangerous. The numerous hospitable traders and reindeerowning natives of Siberia, therefore, were near neighbors, as things look to an arctic explorer. Hadley was constantly saying that his next ambition was to go bach to Wrangell Island to establish himself there permanently.

We talked much of Hadley's colonizing Wrangell Island with my co-operation. I was as much in love with the Arctic after eleven years as he was after twenty five In our mind's eye we could see the northward march of civilization down the great rivers of Canada and Siberia constantly coming nearer that island-dotted Mediterranean between the Old world and the New which we call the Arctic Ocean. We foresaw that air navigation by dirigibles and planes would have a special field in this new development and that the arctic islands would, therefore, acquire a positional value in addition to whatever intrinsic value they might have by reason of their mineral riches or their vegetation and animal life. I took it for certain that the first permanent transarctic air route for fast mail and for passengers in a hurry would be north from London and then south to Tokyo. This route would mean a saving of several thousand miles in distance and, in our opinion, would be preferable in some ways to any other flying route between these two great cities. It would, however, lie far from Wrangell Island and would at first sight appear to have no bearing upon its value. But we knew that for a hundred years the treeless prairies of north America had been considered worthless because they had no trees, and then the point of view had suddenly changed so that the farmers actually began to prefer the prairie to the forest. When that change in mental

stefansson-wrangel-09-26-001-061

45 - 46

attitude appeared in one part of the American continent (about 1820) it spread rapidly to every other part. Similarly, the success of a London to Tokyoflight would almost instantaneously change the world's point of view with regard to the polar regions, making those lands coveted that hsd previously been despised, and that no matter how far they lay from the routes immediately practicable commercially.

It was these conversations with Captain Hadley that led to the first tentative formulation of the plans of the Wrangell Island Expedition which eventually sailed north. Unfortunatley, Hadley could not be in command of it, for he died in San Francisco on influenza during the gret edpisemic of 1916-1919.

stefansson-wrangel-09-26-key

stefansson-wrangel-09-26-key-001

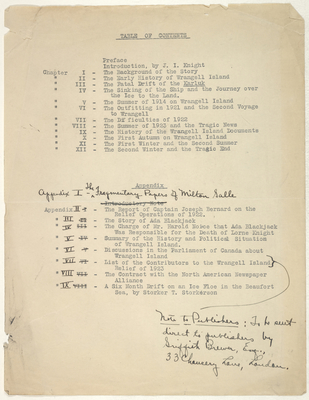

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Preface | ||

| Introduction, by J. I. Knight | ||

| Chapter | I | - The Background of the Story |

| " | II | - The Early History of Wrangell Island |

| " | III | - The Fatal Drift of the Karluk |

| " | IV | - The Sinking of the Ship and the Journey over the Ice to the Land. |

| " | V | - The Summer of 1914 on Wrangell Island |

| " | VI | - The Outfitting in 1921 and the Second Voyage to Wrangell |

| " | VII | - The Dif ficulties of 1922 |

| " | VIII | - The Summer of 1923 and the Tragic News |

| " | IX | - The History of the Wrangell Island Documents |

| " | X | - The First Autumn on Wrangell Island |

| " | XI | - The First Winter and the Second Summer |

| " | XII | - The Second Winter and the Tragic End |

| Appendix | I | - The Fragmentary Papers of Milton Galle |

| Appendix |

II | - The Report of Captain Joseph Bernard on the Relief Operations of 1922. |

| " |

III | - The Story of Ada Blackjack |

| " |

IV | - The Charge of Mr. Harold Noice that Ada Blackjack Was Responsible for the Death of Lorne Knight |

| " |

V | - Summary of the History and Political Situation of Wrangell Island |

| " |

VI | - Discussions in the Parliament of Canada about Wrangell Island |

| " |

VII | - List of the Contributors to the Wrangell Island Relief of 1923 Note to Publishers : To be sent direct to publishers by Griffith Brewers, Esq., 33 Chaucery Lane, London. |

| " |

VIII | - The Contract with the North American Newspaper Alliance |

| " |

IX | - A Six Month Drift on an Ice Floe in the Beaufort Sea, by Storker T. Storkérson |

stefansson-wrangel-09-27

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-001

47

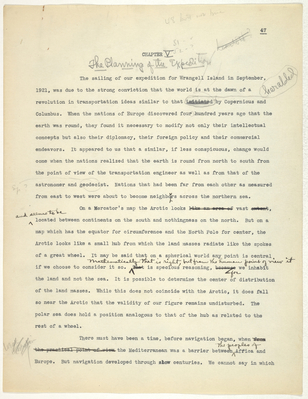

CHAPTER V

The Planning of the Expedition

The sailing of our expedition for Wrangell Island in September, 1921, was due to the strong conviction that the world is at the dawn of a revolution in transportation ideas similar to that initiated heralded by Copernicus and Columbus. When the nations of Europe discovered four hundred years ago that the earth was round, they found it necessary to modify not only their intellectual concepts but also their diplomacy, their foreign policy and their commercial endeavors. It appeared to us that a similar, if less conspicuous, change would come when the nations realized that the earth is round from north to south from the point of view of the transportation engineer as well as from that of the astronomer and geodecist. Nations that had been far from each other as measured from east to west were about to become neighbours across the northern sea.

On a Mercator's map the Arctic looks like an area of vast extent, and seems to be located between continents on the south and nothingness on the north. But on a map which has the equator for circumference and the North Pole for center, the Arctic looks like a small hub from which the land masses radiate like the spokes of a great wheel. It may be said taht on a spherical world any point is central if we choose to consider it so. Mathematically that is right, but from the human point of view it That is specious reasoning, because for we inhabit the land and not the sea. It is possible to determine the center of distribution of the land masses. While this does not coincide with the Arctic, it does fall so near the Arctic that the validity of our figure remains undisturbed. The polar sea does hold a position analogous to that of the hub as related to the rest of a wheel.

There must have been a time, before navigation began, when from the practical point of view the Mediterranean was a barrier between, the peoples of Afica and Europe. But navigation developed through centuries. We cannot say in which

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-002

48

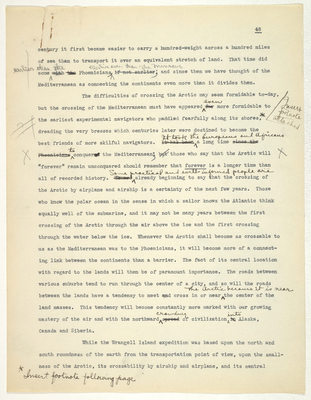

century it first became easier to carry a hundred-weight across a hundred miles of sea than to transport it over an equivalent stretch of land. That time did come earlier than the with the Phoenicians earlier even than the Minoaus; if not earlier and since then we have thought of the Mediterranean as connecting the continents even more than it divides them.

The difficulties of crossing the Arctic may seem formidable to-day, but the crossing of the Mediterranean must have appeared for even more formidable to the earliest experimental navigators who paddled fearfully along its shores; dreading the very breezes which centuries later were destined to become the best friends of more skilful navigators. It has been It took the Europeans and Africans a long time since the Phoenicians to conquered the Mediterranean; butthose who say that the Arctic will "forever" remain unconquered should remember that forever is a longer time than all of recorded history. We are Some practical and well-informed people are a1ready beginning to say that the crossing of the Arctic by airplane and airship is a certainty of the next few years. Those who know the polar ocean in the sense in which a sailor knows the Atlantic think equally well of the submarine, and it may not be many years between the first crossing of the Arctic through the air above the ice and the first crossing through the water below the ice. Whenever the Arctic shall become as crossable to us as the Mediterranean was to the Phoenicians, it will become more of a connecting link between the continents than a barrier. The fact of its central location with regard to the lands will then be of paramount importance. The roads between various suburbs tend to run through the center of a city, and so will the roads between the lands have a tendency to meet and cross in or near the Arctic because it is near the center of the land masses. This tendency will become constantly more marked with our growing mastery of the air and with the northward spread crawling of civilization in into Alaska, Canada and Siberia.

While the Wrangell Island expedition was based upon the north and south roundness of the earth from the transportation point of view, upon the smallness of the Arctic, its crossability by airship and airplane, and its central

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-006

51

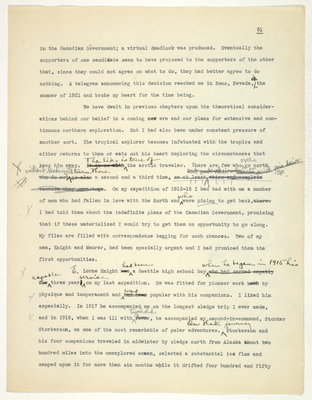

in the Canadian Government; a virtual deadlock was produced. Eventually the supporters of one candidate seem to have proposed to the supporters of the other that, since they could not agree on what to do, they had better agree to do nothing. A telegram announcing this decision reached me in Reno, Nevada, on the summer of 1921 and broke my heart for the time being.

We have dwelt in previous chapters upon the theoretical considerations behind our belief in a coming new era and our plans for extensive and continuous northern exploration. But I had also been under constant pressure of another sort. The tropical explorer becomes infatuated with the tropics and either returns to them or eats out his heart deploring the circumstances that keep him away. Is is so withThe like is true of the arctic traveler. There are few who once go north who do not go alsowithout desiring to return therea second and a third time.or at least whine and complaineat out their heart with vain desire because they cannot go. On my expedition of 1913-18 I had had with me a number of men who had fallen in love with the North and who were pining to get back, there. I had told them about the indefinite plans of the Canadian Government, promising that if these materialized I would try to get them an opportunity to go along. My files are filled with correspondence begging for such chances. Two of my men, Knight and Maurer, had been specially urgent and I had promised them the first opportunities.

E. Lorne Knight was had been a Seattle high school boy who had servered capablywhen he began in 1915 forcapable three year service on my last expedition. He was fitted for pioneer work by physique and temperament and washas been popular with his companions. I liked him especially. In 1917 he accompanied me on the longest sledge trip I ever made, and in 1918, when I was ill with fevertyphoid he accompanied my second-in-command, Storker Storkerson, on one of the most remarkable of polar adventures. On that journey Storkersbn and his four companions traveled in midwinter by sledge north from Alaska about two hundred miles into the unexplored ocean, selected a substantial ice floe and camped upon it for more than six months while it drifted four hundred and fifty

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-007

*See the appendix, post, for an abbreviation of Storkerson's own story of this remarkable adventure. 52

miles, living by hunting the while and trying especially to determine the direction of ice movement in that part of the ocean. During the seventh month Storkerson, the leader, became ill. It was October, the worst part of the year for travel over moving sea ice, and they were then three more than two hundred miles away from land. But because they were complete masters of the technique of winter travel over moving sea ice floes, they got ashore without trouble. The thrilling story of the seven-month drift and the five hundred miles of sledge travel over broken see ice in going forward and back between the composite floe and Alaska is told in the appendix written by Storkerson for my "The Friendly Arctic." With the exception of Storkerson and myself, there was no man living in 1921 not even Nanseu who traveled as many miles on over moving sea ice or who had spent as many days upon it away from a ship as had Knight. Of the great explorers of the past, Perry was the only one who had excelled Knight's record.At twenty-eight he was in age, experience, physical strength an tempermental adaptability are ideal [mau] for the work he so passonately desired to undertake.

Frederick Maurer I saw first in 1912 when he was on a whaling ship wintering in the Arctic north of Canada; in 1913 he became a member of the crew of our Karluk. He was with that ship when it sank some eighty miles north east of Wrangell Island and was one of the men who spent more than six months on Wrangell Island in 1914 after the shipwrecked men landed there. It was he (as we have told in a previous article chapter) who raised the flag at the time British rights to the island ware reaffirmed on July first 1st 1914. Maurer was eager to get back to any part of the Arctic but particularly eager to get back to Wrangell Island, for his knowledge of various other parts of the North led him to consider that as one of the richest and most desirable islands. Like Knight he was at the ideal age of twenty-eight and qualified by experience, temperment, and physical strength. Shortly before I received the telegram from Ottawa saying that the projected expedition had been postponed for at least a year, I had received another wistful letter from Knight in which he said pathetically wistfully: "I have been away from the Arctic nearly two years now, and it has been quite a long two years.”

We have told ina previous chapter that In 1921 it was reported in the press that the Japanese were

stefansson-wrangel-09-27-008

53

believed to be penetrating eastern Siberia with a view to wresting it permanently from the Soviet government of Russia. Some friends of mine who had returned from northeastern Siberia confirmed the actual Japanese penetration at the time and believed in its permanence. With my great admiration for the Japanese, I took it for certain that within a year or two they would realize the coming importance of Wrangell Island and would occupy it. Since they were at that time the allies of Great Britain, it would have been all the more awkward to ask them to leave the island. The most Britain could have done would have been to suggest international arbitration, whereupon it might have been decided that, in spite of original British discovery, an actual Japanese occupation in 1921 or 1922 had more force than a half year of British occupation in 1914.

By a curious accident an old friend, Mr. Alfred J. T. Taylor, of Vancouver, turned up in Reno the day I received the heartbreaking telegram from Ottawa. I was worrying over what appeared to me the shortsightedness of our statesmen and worrying also because it seemed I was going to be unable after all to provide Knight and Maurer with a chance to go north. The appearance of Taylor cheered me, and in an hour my wrecked hopes had been replaced by a plan we thought we could carry through.

Since Wrangell Island was already British, we could keep it British by merely occupying it. As we understood international law, it would make no difference whether such an occupation had been specially ordered by any government so long as the government in question eventually confirmed it. I wired Knight and Maurer to ask whether they would go to Wrangell Island secretly and whether they would exchange their American for Canadian citizenship in order to make the occupation legally effective. Both replied eagerly in the affirmative. Since I was just then engaged under contract on a piece of work that did not allow me a day’s vacation until September, I got Taylor to undertake the actual organization of the expedition. Because the Canadian Government had decided to do