Pages

stefansson-wrangel-09-32-006r

THE FIRST WINTER AND SECOND SUMMER 221

like a seal. After dropping your head on the ice, you should raise it and look around for several seconds before dropping it on the ice again. It is preferable also to wriggle around as if you were itching and trying to scratch yourself on the ice, for seals are infested with a sort of louse which makes them wriggle and scratch continually. With care and patience you should be able to get within fifteen yards of a seal in two hours. An expert hunter gets at least two out of three, and sometimes three out of four of the seals he goes after.

When within shooting distance you wait till the seal raises his head and put a bullet through his brain. Then you drop your rifle and run as fast as you can, for the seal is lying on an incline of wet, slippery ice. The mere shock of instant death may start him slipping and it happens occasionally that the body will slide into the water and be lost. Sometimes you get there just in time to manage to grasp a flipper as it is disappearing. This sliding of the killed animal is the reason why a shot at a hundred and fifty or two hundred yards is impracticable even for the best marksman. You may kill your seal, but you won’t get him. There is enough buoyancy in the lungs and blubber to make him rise, but the original dive will send him twenty or thirty feet diagonally down and he will come up under the ice where you cannot reach him.

Although the practice of this sealing method is a little difficult, the theory of it is so simple that in my expeditions I have several times staked lives on the assumption that a new man can translate the principle into practice in time to avert trouble. I did this first with myself. Having watched the Alaska Eskimos hunting seals by the crawling method and having then listened to their

stefansson-wrangel-09-32-006v

222 THE ADVENTURE OF WRANGEL ISLAND

explanations, I concluded I could do it whenever the necessity arose and did not trouble to practice till the necessity did arise. I followed the same plan with others later. In 1917, for instance, we were 500 miles from the nearest people or supplies when I, who had been doing the hunting, sprained my ankle so badly that I knew I would not be able to walk for a month. Neither of my companions had ever secured a seal by the crawling method and we were in a region where that was the only practicable way. But we all had confidence in our theories and they bundled me up on the sled (no one on any of my expeditions ever rode instead of walking unless he were ill or injured) and we continued traveling away from home. When the occasion arose, I explained over again to one of the men, Karsten Andersen how a seal should be approached and killed. He did exactly as he was told and after an hour’s crawling got his first seal.3

I have always maintained that the method can be learned from a book but I have always added that directions must be followed explicitly and that if the beginner fails it will be because he lacks the patience to follow every rule. A beginner “takes chances,” the seal discovers that the hunter is not a seal, and dives. It is evident from Knight’s diary that the Wrangel party were always in too much of a hurry—they tried to make in one hour an approach that required three. Knight had killed a great many seals on my 1913-1918 expedition, especially in 1918 when he was on the seven-month ice drift with Storkerson two hundred miles north of Alaska, but he had never tried the crawling method. He felt, however, when we discussed this before the Wrangel party sailed

3 See Chapter L, “The Friendly Arctic.” Mr. Noice gives his version of the same circumstances pp. 127-218 “With Stefansson in the Arctic.”

stefansson-wrangel-09-32-007r

THE FIRST WINTER AND SECOND SUMMER 223

that he knew the theory well enough so he could put it in practice whenever necessary. Impatience was, however, his weak point, and it turned out that the first success in the hunt fell to one of the other men who knew the technique only from Knight’s descriptions and mine. I feel sure that Knight understood the source of his failures as well as we do and that he would have curbed his impatience enough to succeed had the situation been pressing, in his opinion. But here, as always in the diary, we see they felt it didn’t matter about any particular hunt or any particular seal—they could always count on succeeding later.

Knight has a typical entry of this spring under date of May 28th. “After breakfast four seals appeared on the ice and Crawford, Maurer and Galle each went after one. Crawford fired at too great a distance and his seal went down. Maurer’s and Galle’s seals went down [(before they had a chance to fire)] and they each lay near the holes, but the seals did not return. A fog then arose and all hands returned to camp. While they were away I saw a great many bands of geese flying north. Three bands of ducks flew west. One band, I am sure, were 'old squaws,’ but the others I was unable to determine. A single tern also flew west. I later took a walk up the .... river and saw the first snipe of the year, a ‘killdeer,’ I think. Saw one fresh fox track. A lemming came out of his hole near camp, making the first one of them that we have seen this season. Needless to say, I am still cooking dog feed.”

By the end of May the Wrangel Island summer had come. The maximum in the shade was 52° on the seacoast, which probably meant that fifteen or twenty

stefansson-wrangel-09-32-007v

224 THE ADVENTURE OF WRANGEL ISLAND

miles inland the temperature was around 70° or 75° in the shade.

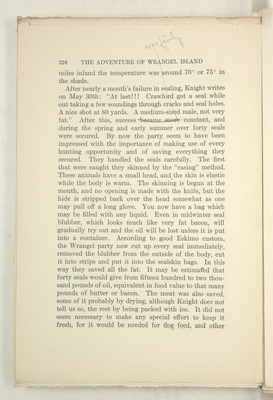

After nearly a month’s failure in sealing, Knight writes on May 30th: “At last!!! Crawford got a seal while out taking a few soundings through cracks and seal holes. A nice shot at 80 yards. A medium-sized male, not very fat.” After this, success was fairly constant, and during the spring and early summer over forty seals were secured. By now the party seem to have been impressed with the importance of making use of every hunting opportunity and of saving everything they secured. They handled the seals carefully. The first that were caught they skinned by the “casing” method. These animals have a small head, and the skin is elastic while the body is warm. The skinning is begun at the mouth, and no opening is made with the knife, but the hide is stripped back over the head somewhat as one may pull off a long glove. You now have a bag which may be filled with any liquid. Even in midwinter seal blubber, which looks much like very fat bacon, will gradually try out and the oil will be lost unless it is put into a container. According to good Eskimo custom, the Wrangel party now cut up every seal immediately, removed the blubber from the outside of the body, cut it into strips and put it into the sealskin bags. In this way they saved all the fat. It may be estimated that forty seals would give from fifteen hundred to two thousand pounds of oil, equivalent in food value to that many pounds of butter or bacon. The meat was also saved, some of it probably by drying, although Knight does not tell us so, the rest by being packed with ice. It did not seem necessary to make any special effort to keep it fresh, for it would be needed for dog feed, and other

stefansson-wrangel-09-32-008r

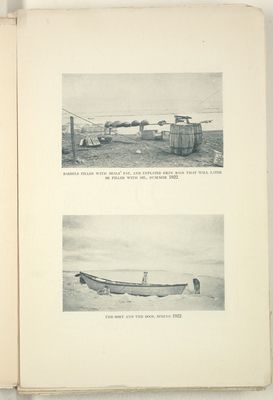

BARRELS FILLED WITH SEALS' FAT, AND INFLATED SKIN BAGS THAT WILL LATER BE FILLED WITH OIL, SUMMER 1922.

THE DORY AND THE DOGS, SPRING 1922.