Pages

1

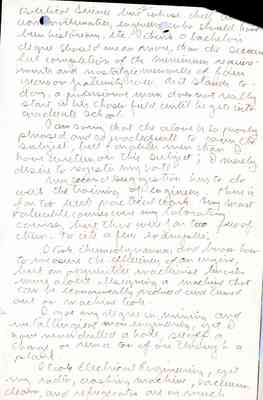

10 April 45

President Donald B. Tresidder Stanford University Palo Alto, California

Dear Sir: In response to your queries of March, 1945:

I am no longer in the military service, having received an honorable discharge for physical disability suffered in the line of duty.

I am planning to do some more graduate work, whether at Stanford or not will depend upon many factors, the post-war faculties and the availability of a teaching position being two of them. I have my engineering degree from Stanford received in June, 1939. I plan to work toward a Doctorate in Engineering, or if the university of my choice does not offer that degree, then a Doctorate of Science. I am pretty well decided that my thesis will be in geophysical field.

As to post-war education, I have one suggestion that is pretty general and perhaps impossible [of?] attainment at present, and one that I think should be recognized as soon as practicable.

The first is a better selective process to be adapted in the first year or two of high school. [Doing?] three and a half years in the army I found too many misfits educationally. Bank tellers with ABs who had majored in

2

Political Science but whose chief [interest?] was mathematics, engineering, who should have been historians, etc. I think a bachelors degree should mean more than the successful completion of the minimum requirements and nostalgic [memories?] of four years or fraternity [scroll?]. As it stands today, a professional man does not really stand in his chosen field until he gets into graduate school.

I am sorry that the above is so poorly phrased and so [ineffectual?] to [cover?] the subject, but far [abler?] men than I have written on this subject; I merely desire to register my vote.

My second suggestion has to do with the training of engineers. There is far too little practical work. My most valuable courses were my laboratory courses, but there were far too few of them. To cite a few examples:

I took thermodynamics and know how to measure the efficiency of an engine, but an apprentice machinist [requires?] more about designing a machine that can be economically produced and [turned?] out on machine tools.

I got my degree in mining and metallurgical engineering, yet I have never drilled a hole, set off a charge, or [send ton?] of [ore?] through a plant.

I took Electrical Engineering, yet my radio, washing machine, vaccuum cleaner, and refrigerator are as much

3

enigma to me as I presume them to be to you.

Tihs criticism is not directed specifically at Stanford, but at our schools all over the country. [My?] academic training has been excellent, the best that money could buy, and yet I find that I have a great deal more theory than I know what to do with. I can discuss [learnedly?] with a man who has had a similar education; the two of us might develop a new and revolutionary engine; but if I were to try and tell an intelligent tool-and-[die?] maker how to construct it, I would be hopelessly lost.

As I look back, it seems to me that too much of my time was wasted in reading assigned chapters and listening to the professor lecture thereon. A man truly interested in his subject will dig out his own [education?] if you guide him to the right sources.

In closing, I recommend less lectures and required reading in engineering courses, more weekly seminars with individual problems, and much much more laboratory and field work.

Yours Truly, Thomas H. Taylor Stanford '41- Engineer