Pages

page_0001

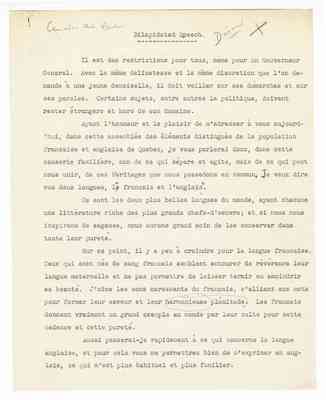

Dilapidated Speech.

ç – la cédille (the cedilla) é – l'accent aigu (the acute accent) â/ê/î/ô/û – l'accent circonflexe (the circumflex) à/è/ì/ò/ù – l'accent grave (the grave accent) ë/ï/ü – le tréma (the trema)

Il est des restrictions pour tous, même pour un Gouverneur General. Avec la même delicatesse et la même discretion que l'on demande à une jeune demoiselle, il doit veiller sur ses démarches et sur ses paroles. Certains sujets, entre autres la politique, doivent rester étrangers et hors de son domaine.

Ayant l'honneur et le plaisir de m' adresser à vous aujourd'hui, dans cette assemblée des éléments distingués de la population française et anglaise de Quebec, je vous parlerai done, dans cette causerie familière, non de ce qui sépare et agite, mais de ce qui peut nous unir, de ces héritages que nous possedons en commun. Je veux dire vos deux langues, la français et l'anglaise.

Ce sont les deux plus belles langues du monde, ayant chacune une littérature riche des plus grands chefs-d'oeuvre; et, si nous nous inspirons de sagesse, nous aurons grand soin de les conserver dans toute leur pureté.

Sur ce point, il y a peu à craindre pour la langue française. Ceux qui sont nés de sang français semblent entourer de révérence leur langue maternelle et ne pas permettre de laisser ternir ou amoindrir sa beauté. J'aime les sons caressants du français, s'alliant aux mots pour former leur saveur et leur harmonieuse plénitude. Les Français donnent vraiment un grand exemple au monde par leur culte pour cette cadence et cette pureté.

Aussi passerai-je rapidement à ce qui concerne la langue anglaise, et pour cela vous me permettrez bien de m'exprimer en anglais, ce qui m'est plus habituel et plus familier.

page_0002

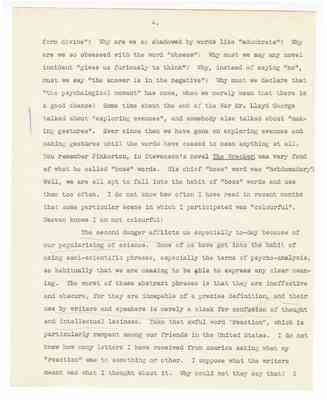

2.

I am going to offer you a few reflections upon a thing with which we are all concerned - our English language. It is spoken today by about half the dwellers on the earth's surface, it contains some of the greatest literature ever written, it draws from innumerable sources, and has very stiff standards of its own, and at the same time it is always changing, for, like all living things, it keeps in touch with every age. Today both our spoken and written language are full of new words and idioms. It contains, for example, many new technical terms from new sciences. It draws a good deal from slang. A slang phrase is generally a striking metaphor which, if it is really needed, becomes sooner or later embodied in our ordinary language. We can never have enough of them if they are good. If English ever stopped taking in new words, phrases, and metaphors it would soon be a dead thing. The greatest writer who ever lived was a tremendous innovator. The young gentlemen from the Universities must have thought Shakespeare a very vulgar innovator in his language, but what would the English language be without Shakespeare's colossal novelties? Another sign of life in our tongue is that in different societies, and different parts of the earth, while keeping its essential character it has its own local idioms. For example, Canadian journalism, if I may be allowed to say so, is good standard English, but, since I came to this country, I have learned several new uses of words , such as "slate" and "score" and "probe", all very useful in their way.

But though our language is constantly changing it must change within fixed limits. We must always keep it a living and organic thing, with a strong internal structure. It must never be allowed to become limp and slack. I do not mean that our writing should

page_0003

3.

be formal and pedantic. What we call a colloquial style may have a very firm structure behind it. But once we forget structure, what the French call ordonnance, then the virtue goes out of our speech. Three thousand years ago Homer talked about "articulate-speaking men". He was thinking of certain barbarous and primitive tribes who were not articulate. Our ancestors in the Stone Age cannot have been articulate. Their language was probably a fluid, shapeless thing, incapable of expressing any but the most elementary emotions. So if we cease to be really articulate, if we let our speech and writing become loose and shapeless and badly screwed together, then we are losing one of the chief benefits of civilisation. We are slipping back to barbarism.

I want to suggest to you one or two dangers which beset us today, and which I think we ought to guard against.

The first is the use of what I call jargon; that is words and metaphors which have no exact, clear-cut meaning. They may have been all right at the beginning, but the virtue has gone out of them now. They have now become empty phrases, mere counters which have lost the freshness of the living language. You find this in every profession. It is found in t he correspondence of business men and lawyers; it is rampant in Blue books and Government reports; it is very common in the Army, as those of you who served in the War will remember. In journalism I think the fault comes chiefly from using phrases which have gone stale and meaningless from constant repetition. For example - The man who first said that someone was "of the male persuasion" said something funny, but to repeat it constantly gets on one's nerves. Why must every foundation be "well and truly laid"? Why must we call women "the softer sex"? Why must we speak of the body as "the human

page_0004

4.

form divine"? Why are we so shadowed by words like "adumbrate"? Why are we so obsessed with the word "obsess"? Why must we say any novel incident "gives us furiously to think"? Why, instead of 'saying "no", must we say "the answer is in the negative"? Why must we declare that "the psychological moment" has come, when we merely mean that there is a good chance? Some time about the end of the War Mr. Lloyd George talked about "exploring avenues", and somebody else talked about "making gestures". Ever since then we have gone on exploring avenues and making gestures until the words have ceased to mean anything at all. You remember Pinkerton, in Stevenson's novel The Wrecker, was very fond of what he called "boss" words. His chief "boss" word was "hebdomadary". Well, we are all apt to fall into the habit of "boss" words and use them too often. I do not know how often I have read in recent months that some particular scene in which I participated was "colourful". Heaven knows I am not colourful!

The second danger afflicts us especially today because of our popularising of science. Some of us have got into the habit of using semi-scientific phrases, especially the terms of psycho-analysis, so habitually that we are ceasing to be able to express any clear meaning. The worst of these abstract phrases is that they are ineffective and obscure, for they are incapable of a precise definition, and their use by writers and speakers is merely a cloak for confusion of thought and intellectual laziness. Take that awful word "reaction", which is particularly rampant among our friends in the United States. I do not know how many letters I have received from America asking what my "reaction" was to something or other. I suppose what the writers meant was what I thought about it. Why could not they say that? I

page_0005

5.

opened an American novel the other day and read that the heroine had come to New York "to glimpse contacts and sense reactions". I immediately shut that novel. So I hope we will be chary about these spurious counters - "isms" and "ologies", "inhibitions", "complexes", "repressions"; and say what we have to say in the simple, vivid language of ordinary life. Unless your object is to avoid the law of libel, don't say that a man has a complex of misappropriation", but that he is a thief; don't say that he "dabbles in terminological inexactitudes", but that he is a liar. Do not, I beseech you, turn the first sentence of the Scots Shorter Catechism, "Man's chief end is to glorify God" into "The supreme objective of humanity is to further the realisation of the Absolute Will," which does not mean so much, if it means anything at all. The English language has a noble concreteness not to be paralleled, I think, by any other tongue. It is our business to take advantage of what the gods have given us. I am inclined to think that more good writing today is spoilt by sudden lapses into meaningless philosophical abstractions and loosely used scientific terms than by any other fault of style.

There is a third danger, which does not depend upon the misuse of words so much as upon the complete breakdown of structure and syntax. I should call it the jazz style, which forgets that all good writing and speaking must have structure and shape, and must obey certain rules. This is a fault just as much of the highbrows as of the ordinary man. A great deal of our modern poetry in England rejoices in having no verbs, and the reader has to puzzle it out as if it were an acrostic. Surely that is not any kind of poetry! There is a certain type of modern fiction which is largely a series of interjections,