Pages

1

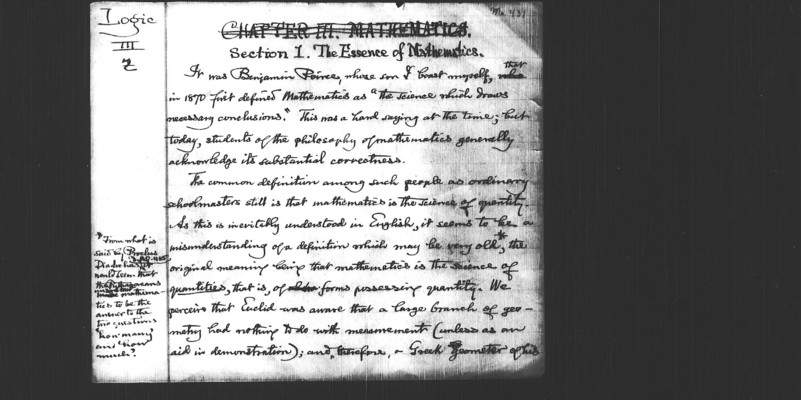

Section 1. The Essence of Mathematics.

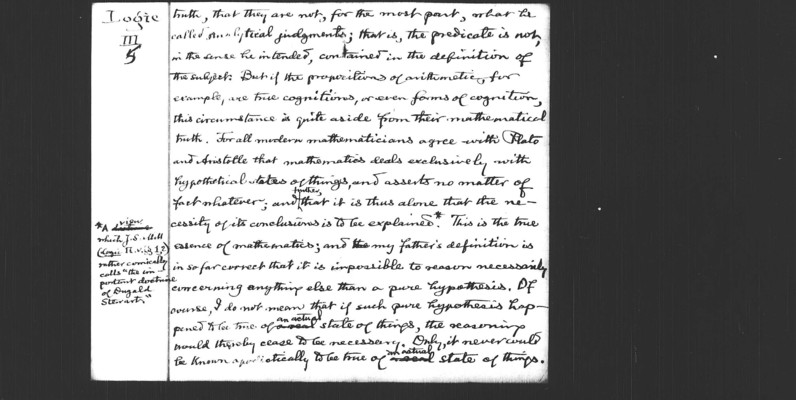

It was Benjamin Peirce, whose son I boast myself, that in1870 first defined mathematics as "the science which grows necessary conclusions." This was a hard sayingat the time; but today, students of the philosophy of mathematics generally acknowledge its substantial correctness.

The common definition among such people as ordinary schoolmasters still is that mathematics is the science of quantity. As this is inevitably understood in English, it seems to be a misunderstanding of a definition which may be very old*, the original meaning being that mathematics is the science of quantities, that is, of forms possessing quantity. We perceive that Euclid was aware that a large branch of geometry had nothing to do with measurements (unless as an aid in demonstration); and, therefore, a Greek geometer of his

*From what is said by Proclus Diadochus A.D. 485 would mean that the Pythagoreans understood mathematics to be the answer to the two questions 'how many' and 'how much'?

2

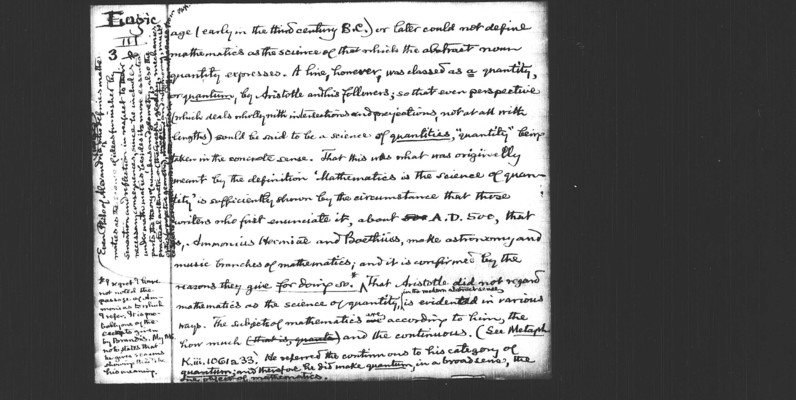

age (early in the third century B.C.) or later could not define mathematics as the science of that which the abstract [no?] quantity expresses. A line, however, was classed as a quantity, or quantum, by Aristotle and his followers; so that even perspective (which deals wholly with intersections and projections, not at all with lengths) could be said to be a science of quantities, "quantity" being taken in the concrete sense. That this was what was originally meant by the definition 'Mathematics is the science of quantity' is sufficiently shown by the circumstance that these writers who first enunciate it, about A.D. 500, that is, Ammonius Hermiae and Boethius, make astronomy and music branches of mathematics; and it is confirmed by the reasons they give for doing so*.^ That Aristotle did not regard mathematics as the science of quantity, ^in the modern abstract sense, is evidented in various ways. The subjects of mathematics are, according to him, the how much and the continuous. (See Metahph. K.iii.1061a33.) He referred the continuous to the category of quantum, and therefore he did make quantum, in a broad sense, the one [??] of mathematics.

[notes on the side:] Even Philo of Alexandria, who defined mathe matics as the science of ideas furnished by sensation and reflection in respect to their necessary consequences, since he includes under mathematics, besides its more essential parts, the theory of numbers and geometry, also the practical arithmetic of the Greeks, geodesy, mechanics, optics (or projective geometry), magic and astronomy, must [??]

*I regret I have not noted the passage of Ammonius to which I refer. It is probably one of the [??] given by [B?]. My MS. [no?] states that he gives reasons showing [?] to be hos meaning.

3

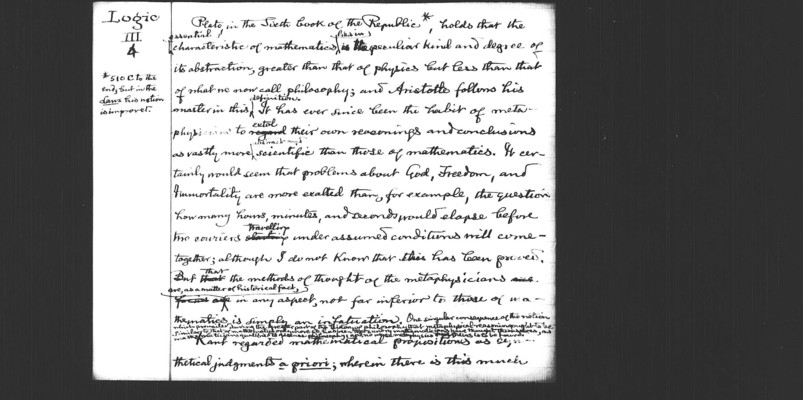

Margin Sidebar: Logic III [4?] * 510 C to the end, but in the [Laws?[ this notion is improved.

Plato, is the Sixth book of the Republic*, holds that theessential characteristic of mathematics, [Pikes in] [speculiar?] kind and degree of its abstraction, greater than that of physics but less than that of what we now call philosophy; and Aristotle [follwers?] his smarter in this (definition). It has ever since been the habit of [metaphysicians?] to extol their own reasonings and conclusions as vastly more, scientific [(abs?)] than those of mathematics. It certainly would seem that problems about God, Freedom, and Immortaility are more exalted than, for example, the question how many hours, minutes, and seconds would elapse before [tm?] couriers traveling under assumed conditions will come-together; although I do not know that this has been [gor?]. But that the methods of thought or the metaphysicians (crossed out word) are as a matter of historical fact, (2 crossed words), in any aspect, not far inferior to those of [wa?] the [matics?] is simply an infatuation. One singular consequence of the notion which [pre?] during the greater part of the [b?] of philosophy that metaphysical reasoning [sp?] to be similar to that of mathematics only have [has been.......?] [Kant?] regarded mathematical peopositions as [synthetical?] judgments a [gri?]; wherein there is this much

5

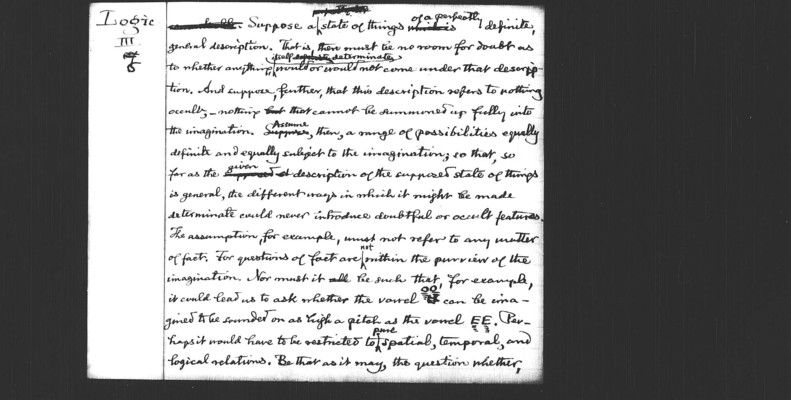

Suppose a state of things of a perfectly definite, general description. That is, there must be no room for doubt as to whether anything, itseld determinates, would or would not come under that description. And suppose, farther, that this description refers to nothing occult, - nothing that cannot be summoned up fully into the imagination. S̶u̶p̶p̶o̶s̶e̶ Assume, then, a range of possibilities equally definite and equally subject to the imagination; so that, so far as the given description of the supposed state of things is general, the different ways in which it might be made determinate could never introduce doubtful or occult features. The assumption, for example, must not refer to any matter of fact. For questions of fact are not within the [purview?] of the imagination. Nor must it a̶l̶l̶ be such that, for example, it could lead us to ask whether the vowel oo can be imagined the sounded on as high a pitch as the vowel EE. Perhaps it would have to be restricted to [pme?] spatial, temperal, and logical relations. Be that as it may, the question whether,