Pages

31

Logic 39

nature of argument. Namely, Aristotle argues that there must be certain first principles science because every scientific demonstration reposes upon a general principle as a premiss. If this premiss be scientifically demonstrated in its turn that demonstration must again have been based upon general principle as its premiss. Now there must have been a beginnning od the process and therefore a first demonstration reposing upon an indemonstrable mremiss. This is an argument like the Achilles and Tortoise argument of eno except that instead of going forward in time it goes backwards. If we were to admit that the process of thought in the mind is reallt composed of distinct parts corresponding to the arguments of the logical representations of it each requiring a distinct effort of thought then indeed we should have to admit Aristotle reasoning unless we were prepared to admit that a endless series of

32

Logic 32

could actually be performed in a finite tome just as we should have to admit that Achilles could never over take the tortoise if he had to resolve to run to where the tortoise there was and having arrived there to form a new resolution to run to the point at which the tortoise had then attained. This would involve the assumption that Achilles would not now unless he saw the tortoise ahead of him. In like manner the assumption that thought the reasoning process as it is the mind consists of a succession of distinct arguments each having a previously thought premiss involves the assumption that reasoning cannot begin with the very perceptions of sense since in thse perceptions the process of thought has not yet begun so that they do not contain any judgements capable of being exactly represented by prepositions

33

Logic 33

or assertions. If that be so there must already be a first premiss. But there is no necessity for supposing that the process of thought as it takes place in the mind is always cut up into distinct arguments. A man goes through a precess of thought. Who shall say what the nature of that process was? He cannot for during the process he was occupied with the object about which he was thinking not with himself nor with his motions. Had he been thinking of these things his current of thought would have been broken up and altogether modified for he must then have after noted from one subject of thought to another. Shall he endevour after the cource of thought is done to recover it by repeating it on this occasion intercepting it and noting what he had last in mind? Then it will be extemely likely that he will learn able to interrupt it at times when the movement of thought

34

Logic 34

is considerable he will most likely be able to do so but only at times when that movement was so slowed down that in endeavoring to tell himself what he had in mind he loses sight of that movement altogether especially with language at hand to represent attitudes of thought but not movements of thought. Practically when a man endeavors to date what the process of his thought has been after the process has come to an end he first asks himself to what conclusion he has come. That result he formulates in an assertion which we will assume has some sort of likeness - I am inclined to think only a very conventionalized one - with the attitude of his thought at the cessation of the motion. That having been ascertained he next asks himself how he is justified in eing so confident of it and he proceeds to cast about for a sentence expressed in words which

35

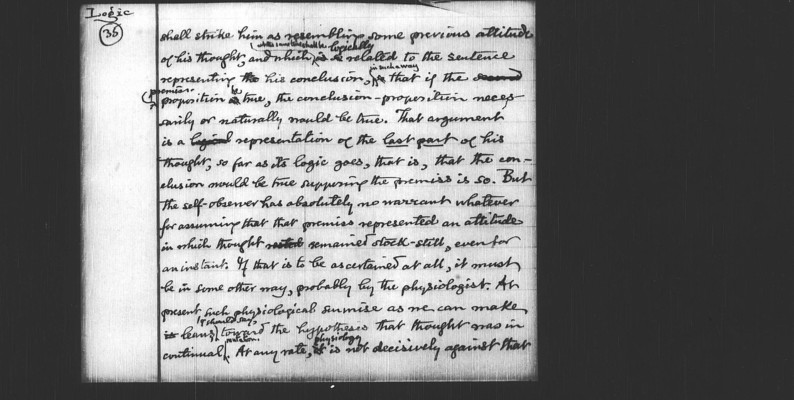

Logic 36

shall strike hime as resembling some previous attitude of his thought and which while some shall be logically related to the sentence representing his conclusion in such a way that if the premiss proposition be true the conclusion proposition necessarily or naturally would be true. That argument is a logical representation of the last part of his thought so far as its logic goes that is that the conclusion would be true supposing the premiss is so. But the self-observer has absolutely no movement whatever for assuming that that premiss represented an attitude in which thought remained stock-still even for an instant. If that is to be ascertained at all it must be in some other way probably by the physiologist. At present such physiological surpise as w can make [?eans]. It should say towards the hypothesis that thought was in continual mutation. At any rate physiology is not decisively against that