Pages

11

{Left margin, top of page: "Logic 11"}

the extremely loose reasoning of all the philosophers. It was a matter open to the remark of every mathematician, even before Weierstrass {Refers to Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass (1815-1897).}, when mathematical reasoning was far less strict than it has since become. the more recent philosophers show no improvement in this respect. You may search the whole library of modern metaphysics from Descartes to Royce and hardly find a single argument which does not leave room to drive a coach through it, commodiously. The effect upon the minds of those who have been nourished on such food mainly becomes deplorably patent to everybody who finds himself in contact with them. Their natural sense of logic is enfeebled and diseased. I am confident I detect something of this even in the majority of those young men who become known me only as having paid particular attention to philosophy

12

{Left margin, top of page: "Logic 12"}

in the universities; although there are some whose logical instincts have been too robust to be so easily debilitated.

{Left margin, next to first two sentences of the paragraph below: "Concrete science among the Greeks."}

The Greek philosophers could not be persuaded that minute analysis was proper in physical science. Born Aegelian sensualists, they could not divest themselves of their belief that no worse way of getting at any comprehension of a flower by picking it to pieces, and so spoiling the flower. What was the result? Manifold have been the theories to account that have been successfully offered, considered, and rejected, to account for the non-success of the Greeks in physics. That the vast intellect of an Aristotle, so great in zoölogy, in the science of politics, in rhetoric, in the history of philosophy; so gigantic in ethics, logic, metaphysics, and psychology; should, in physics, have

13

{Left margin, top of page: "Logic 13"}

sunk into abject inferiority to the cranks of modern times, the refuters of Newton, the proposers of perpetual motions; has hitherto not been adequately explained. But what better account of the matter could one desire than that in physics the Hellenic element of Aristotle's nature, that Greek estheticism which forbade analysis and required that the phenomenon should be contemplated in its concreteness here governed him. that this was the cause is shown by the fact that all the other Greeks who shared the same prejudice were equally unsuccessful, while the few who did not share it, Hipparchus, Eratosthenes, Posidonius, Ptolemy, Archimedes, were eminently successful in the physical sciences. In zöology, Asclepial Aristotle, scion of a family whose every member, from the further prehistoric times, had been trained in medicine from childhood up, shared no Hellenic repugnance to dissection. Nor did that repugnance

{Left margin, bottom of page: "Mem. Before this goes to press, I have to go over three books: 1. Barthélemy St. Hilaire's Ed. of Arist. {Aristotle}. Historial Animal. 2. Littré's Hippocrates. 3 The best German history of medicine."}

14

{Left margin, top of page: "Logic 14"}

ever extend to the non-sensuous object with which Aristotle dealt in the sciences in which he most excelled.

In the northern Europe of the scholastic ages, the nullity of physics was due to a different cause, explicitly set forth by Roger Bacon. Logic and metaphysics were studied with a considerable degree of minuteness and accuracy; so that, in spite of a barbaric civilization and other unfavorable influences, sufficiently obvious, they reached an excellence which our own generation has not been able to appreciate.

Our physical science, whatever extravagant historicists may say, seems to have sprung up uncaused except by man's intelligence and nature's intelligibility, which never could before be operative because it was not studied minutely. But modern philosophy had no such divine birth. On the contrary, it pays the usual

15

{Left margin, top of page: "Logic 15"}

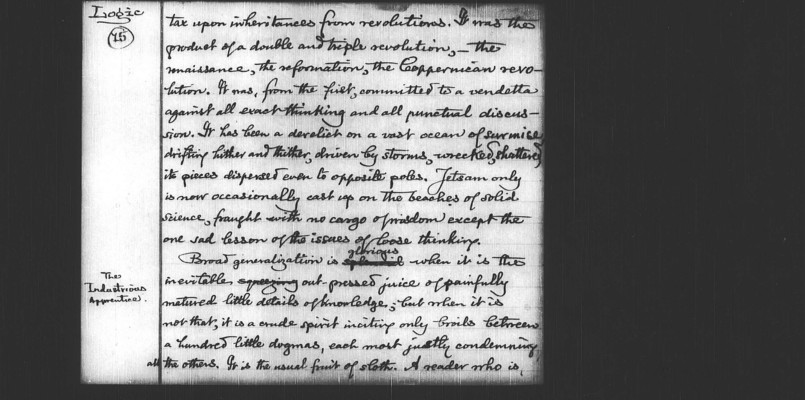

tax upon inheritances from revolutions. It was the product of a double and triple revolution, -- the renaissance, the reformation, the Coppernican revolution. It was, from the first, committed to a a vendetta, committed to a vendetta against all exact thinking and all punctual discussions. It has been a derelict on a vast ocean of surmise, drifting hither and thither, driven by storms, wrecked, shattered, its pieces dispersed even to opposite poles. Jetsam only is now occasionally cast up on the beaches of solid science, fraught with no cargo of wisdom except one sad lesson of the issues of loose thinking.

{Left margin, second line of the paragraph below: "The Industrious Apprentice."}

Broad generalization is splendid glorious when it is the inevitable squeezing out-pressed juice of painfully matured little details of knowledge; but when it is not that, it is a crude spirit inciting only broils between a hundred little dogmas, each most justly condemning all the others. It is the usual fruit of sloth. A reader who is