Pages

21

40

The first thing to be taken into consideration is the general upshot of Kant's Critic of the Pure Reason. The first step of Kant's thought,— the first moment of it, if you like that phraseology,— is to recognize that all our knowledge is, and forever must be, relative to human experience and to the nature of the human mind. That conception being well digested, the second moment of the reasoning becomes evident, namely, that as soon as as it has been shown concerning any conception that it is essentially involved in the very forms of logic or other forms of knowing, from that moment there can no longer be any rational hesitation about

22

42

fully accepting that conception, as valid for the universe of our possible experience. To repeat an example I have given before, you look at an object and say “that is red.” I ask you how you prove that. You tell me you see it. Yes, you see something; but you do no see that it is red; because that it is red is a proposition; and you do not see a proposition. What you see is an image and has no resemblance to a proposition, and there is no logic in saying that your proposition is proved by the image. For a proposition can only be logically based on a premiss and a premiss is a proposition. To this you very properly reply, with Kant's aid, that my objections allege what is perfectly true

23

44

but that instead of showing that you have no right to say the thing is to read they conclusively prove that you have logically justified in doing so. At this point, the idealist appears before the tribunal of your reason with the suggestion that since these metaphysical conceptions, that repose upon their being involved in the forms of logic are only valid for experience and since all our knowledge is relative to the human mind, they are not valid for things as they objectively are; and since the conception of existence is preëminently a conception of that description, it is a mere fairy-tale to say that outward objects exist, the only objects of possible experience being our own ideas. Hereupon

24

46

comes the third moment of Kant's thought, which was only made prominent in the Second Edition, not, as Kant truly says, that it was not already in the book, but that it was an idea in which Kant's mind was so completely immersed that he failed to see the necessity of making an explicit statement of it until Fichte misinterpreted him. It is really a most luminous and central element of Kant's thought. I may say that it is the very Sun round which all the rest revolves. This third moment consists in the flat denial that the metaphysical conceptions do not apply Kant never said that. What he said is that those conceptions do not apply

25

48

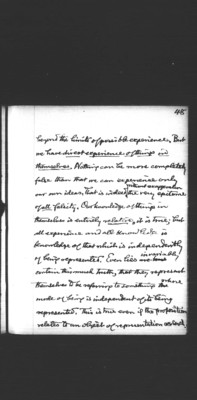

beyond the limits of possible experience. But we have direct experience of things in themselves. Nothing can be more completely false than that we can experience only our own ideas. That is indeed without exaggeration the very epitome of all falsity. Our knowledge of things in themselves is entirely relative, it is true; but all experience and all knowledge is knowledge of that which is independently of being represented. Even lies invariably contain this much truth, that they represent themselves to be referrning to something whose mode of being is independent of it being represented. This is true even if the proposition relates to an object of representation as such.