Description

When the American Civil War began in the spring of 1861, many northerners and southerners expected the conflict to be short, settled after a rapid military campaign and perhaps one great battle. When those expectations proved incorrect, Union military authorities began conducting broad offensive operations designed to capture key locations within the Confederacy. The first targets held military or political value, such as fortifications, port cities, and capitals. Union armies advancing toward those objectives began capturing pro-secessionist communities. Because federal activities in the South focused on military objectives, Union armies initially had little guidance on how to govern the Confederate areas they occupied. As a result, federal officers relied upon their own interpretation of law and their military authority. Many took a conservative approach, enacting few changes to the local community, while others governed with a heavy hand—either as punishment to secessionists or to enact their favored political policies. One such example included General John C. Frémont’s declaration of martial law and emancipation of slaves in Missouri. The order was quickly overturned by President Abraham Lincoln’s administration, but the incident revealed the varied actions that occurred in pro-secessionist areas occupied by Union forces.

As the war progressed, Union armies advanced deeper into the Confederacy. Lincoln began developing plans for reconstruction and reconciliation of Union-controlled areas, but restructuring local governments was only part of the effect occupation had on Southern communities. Federal armies needed supplies. Union officers acquisitioned resources within occupied areas—sometimes with payment, other times by confiscation—to feed and support their military forces. In cases where Union troops could not maintain a permanent presence, they burned or otherwise destroyed Southern crops, buildings, and railroads to deny their use by Confederates.

Union-occupied areas of the South also saw an influx of northern businessmen anxious to capitalize on Southern resources. Since the Union navy blockaded Confederate ports and prevented exports to Europe, many Southerners had surplus supplies and limited market options. Cotton speculators shadowed Union armies—and in some cases colluded with federal military officials—to negotiate with these desperate Southern planters to send their crop north. This illicit business practice became rampant in occupied areas, prompting the War Department to establish rules for business transactions within Union lines. Illegal trade continued. In December 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant issued General Orders No. 11 in response to continued concerns about market speculation in occupied portions of the Confederacy. The order was highly controversial because it unfairly blamed the Jewish population for the problematic business practices and called for the expulsion of all Jewish citizens from his military department. The Lincoln administration immediately rescinded the order, but Grant lived with the negative effects of his discriminatory proclamation for the rest of his life. The event highlighted the tensions of market speculation and illicit trade in Union occupied areas.

The most significant effect Union occupation had on Southern communities was the disruption of slavery. Enslaved African Americans fled to Union armies to escape bondage. Early in the war, Union commanders had no guiding policy for handling runaway slaves. Some returned them to their owners; others, with abolitionist principles, happily facilitated their escape north or protection behind Union lines. However, in May 1861, Union general Benjamin Butler developed a new legal approach to fugitive slaves when a small number sought refuge within his lines at Union-occupied Fort Monroe, Virginia. He refused to return them to their secessionist owner, declaring them “contraband of war”—property which could be confiscated according to laws of war. News of this policy saw widespread support across the North, as punishment to secessionists but also as a practical way to deny the Confederacy its chief source of labor. The United States Congress soon followed Butler’s actions with legislation authorizing Union armies to confiscate Confederate property and slaves. As the war continued, federal policies against slavery expanded, until Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which declared all slaves within Confederate areas forever free. Even with Lincoln’s hope for a quick restoration and reconciliation of the Union, occupied areas of the South were forever changed during the Civil War.

At the end of the war, the United States Army occupied the whole South. However, sustained occupation was not possible, especially as the War Department reduced the army by discharging hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers. The army kept troops in the south to enforce federal law—especially to protect African American rights—as former Confederates began to move back into local political offices. However, their role in Southern communities declined until 1877, when southern Democrats and Republican supporters of presidential candidate Rutherford Hayes agreed upon a plan to withdraw the last United States soldiers from the South and end Reconstruction. Federal occupation of the South, which had begun in 1861 in response to secession and the Civil War, was over. (Wikipedia; National Park Service; Army Heritage Center Foundation)

See also: https://www.armyheritage.org/soldier-stories-information/the-occupation-of-the-south/

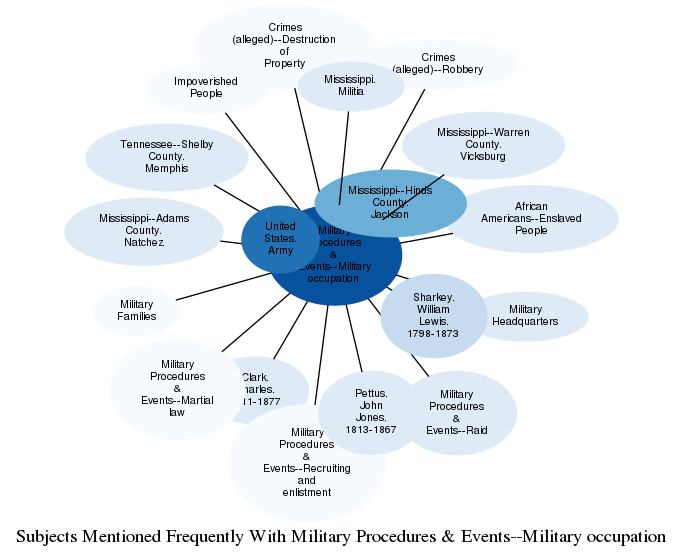

Related Subjects

The graph displays the other subjects mentioned on the same pages as the subject "Military Procedures & Events--Military occupation". If the same subject occurs on a page with "Military Procedures & Events--Military occupation" more than once, it appears closer to "Military Procedures & Events--Military occupation" on the graph, and is colored in a darker shade. The closer a subject is to the center, the more "related" the subjects are.